December 1: The Futures of the Maya Past

Does the history of Maya archaeology look different when written from Guatemala rather than North America? What role has and does Guatemalan nationalism play in interest in the ancient Maya past? How have the roles for Guatemalan archaeologists, women, and indigenous people in Maya archaeology changed over the past century? How might (or should) they continue to change?

December 1: Agenda

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Begin with a conversation/Q&A session with our invited speakers, Dr. Jessica MacLellan and Alejandra Roche Recinos (don't forget to post questions for our guests to the dedicated Canvas questions forum by 12 PM!)

2. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to also post to the Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!).

3. Workshop the peer reviews of Shorthand rough drafts in Breakout Groups and discuss highlights from the peer review process with the class as a whole.

Order of Readings

1. Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, “Archaeology in Guatemala: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist”

2. Jessica MacLellan, Melissa Burnham, and María Belén Méndez Bauer, "Community Engagement around the Maya Archaeological Site of Ceibal, Guatemala"

3. Iyaxel Ixkan Anastasia Cojtí Ren, "The Experience of a Mayan Student"

4. Optional: Bárbara Arroyo, "Juan Pedro Laporte (1945-2010)" (in Spanish)

5. Optional: Pia Flores, "Dos arqueólogas: Nuestro trabajo es mas que lo que salió en NatGeo (y no es para el turismo)" (in Spanish)

Readings for Discussion

Although there are fewer assigned readings than usual for this week, the theme for our final class brings together many of the topics that we have covered over the course of the quarter. The costs and consequences of imperialism and exploitation have surfaced again and again—in the destruction caused by early archaeological projects; in the creation of a market for looted antiquities; in the exoticism and appropriation of Mayan Revival architecture, New Age spiritualism, and tourism's insistence on an ideal of "pristine" authenticity. But what is the solution? As a history (and often a critique) of the development of Maya archaeology, this course inevitably forces us to consider where the field might (or should) be headed in the future.

The readings assigned for this week review the history of archaeology in Guatemala, detail one project's various efforts to engage with local communities near the archaeological site of Ceibal, and recount the personal experiences of a Maya-K'iche' woman in archaeology. As you read, pay attention to the ways in which both the national history of archaeology, contemporary local economic interests, and individual careers in Guatemala are deeply, perhaps inextricably, entangled with foreign (especially American) influences. Are there alternatives?

1. Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, “Archaeology in Guatemala: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist”

Oswaldo Chinchilla, a Guatemalan archaeologist, is currently a professor of anthropology at Yale University. Chinchilla is a specialist in ancient Maya art, myth, religion, and writing. He has also conducted archaeological investigations focused on settlement patterns and urbanism at Cotzumalhuapa, a site on the Pacific Coast of Guatemala.

Chinchilla received his PhD from Vanderbilt University. Before moving to Yale, he was a professor at the Universidad de San Carlos in Guatemala and curator at the Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala. He has written several articles and book chapters on the history of archaeology in Guatemala and on the creation of the National Museum in Guatemala.

In this chapter from The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology, Chinchilla reviews the history of archaeology in Guatemala using a framework developed by archaeologist and historian Bruce Trigger. Trigger, who has written the definitive history of archaeology in his 732-page book, A History of Archaeological Thought, proposed that there are three different kinds of archaeology, which develop in relation to the context in which they are practiced: nationalist, colonialist, and imperialist. Chinchilla both uses Trigger's categories to chronicle the history of archaeology in Guatemala and argues against a rigid framework by highlighting how the distinctions between nationalist and colonialist or colonialist and imperialist are easily blurred.

Access a PDF of Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos's, “Archaeology in Guatemala: Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist” here.

As you read Chinchilla's chapter, think about how the history of Maya archaeology has been presented in other texts we have read this quarter (e.g., Stephen Black's article from Week 2 or David Webster's chapter from last week). Note how most chronicles begin with Stephens and Catherwood—despite the fact that state-sponsored expeditions and even excavation had taken place in Guatemala well before Stephens and Catherwood's travels. Think too about the way Chinchilla describes the entwined interests of the United Fruit Company and archaeologists at the site of Quirigua in relation to Leandro Katz's Paradox from last week.

After reading Chinchilla's chapter, ask yourself the questions outlined for this week: Does the history of Maya archaeology look different when written from Guatemala rather than North America? What role has and does Guatemalan nationalism play in interest in the ancient Maya past?

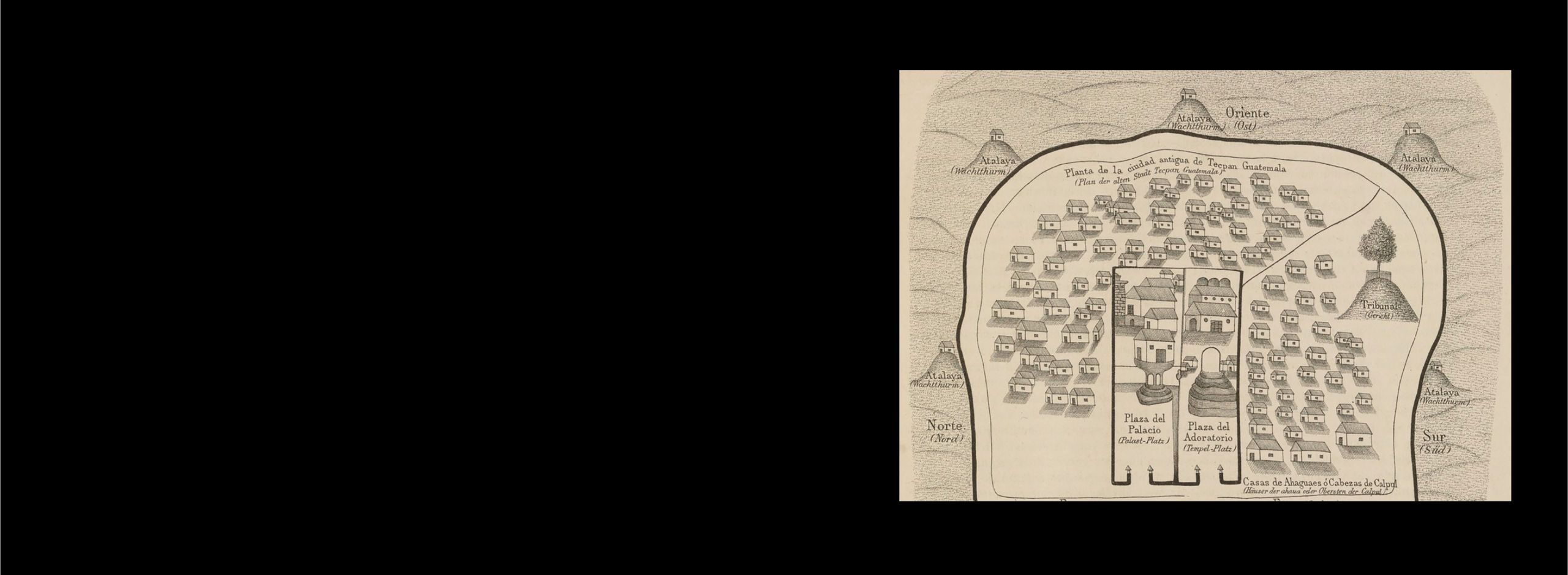

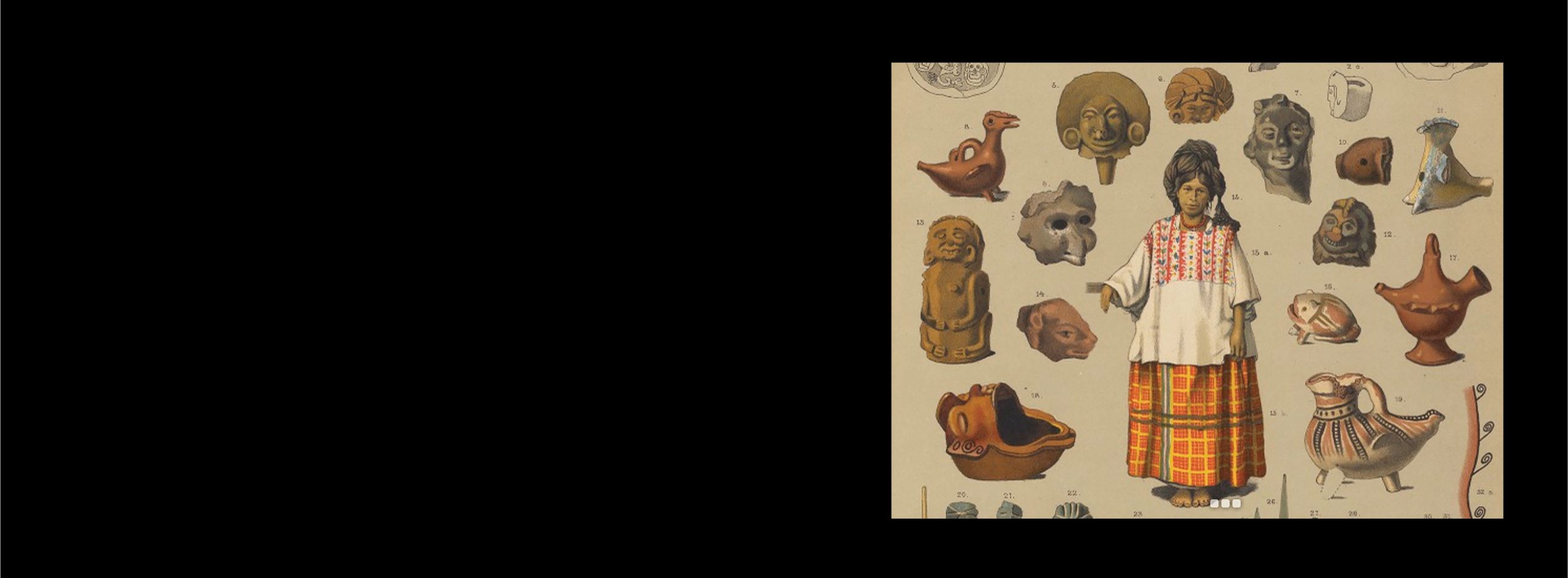

Background images: 1) Plan of the city of Tecpan, Guatemala, including the ruins of Iximche' at center (an 1889 copy by Otto Stoll from Antonio Fuentes y Guzmán's 1690 Recordación Florida); 2) View of a ruined compound at the site of Utatlán (from the archaeological expedition sponsored by the Guatemalan government). Lithograph by Julián Falla, 1834; 3) A Maya woman surrounded by archaeological artifacts, drawing a connection between the past and present. Image by Otto Stoll, 1889.

2. Jessica MacLellan, Melissa Burnham, and María Belén Méndez Bauer, "Community Engagement around the Maya Archaeological Site of Ceibal, Guatemala"

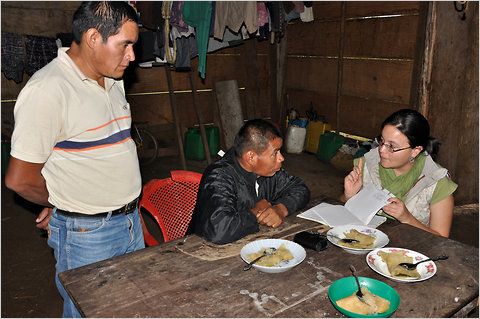

In this article, Jessica (Jess) MacLellan and her collaborators discuss various efforts that the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project has made to engage with and contribute to the local Q'eqchi' Maya village of Las Pozas. Those efforts range from seasonal employment in archaeological excavation to ecotourism plans to a microsavings project. The article also describes the many challenges faced by Peten communities and by the anthropologists and archaeologists interested in both local economic improvement and cultural heritage preservation. As you will see in the article, many of the projects designed by the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project have had little or short-term success.

Access a PDF of Jessica MacLellan, Melissa Burnham, and María Belén Méndez Bauer's, "Community Engagement around the Maya Archaeological Site of Ceibal, Guatemala" here.

MacClellan and her colleagues' frank discussion of the difficulties, errors, and potential improvements with respect to their own engagement projects is a refreshing counter-narrative to the usual celebrations of any efforts made by archaeologists to engage local communities. But it also raises important questions. What kinds of activities should be undertaken by foreigners on behalf of indigenous and ladino communities? Who should design and who should benefit from those efforts? The article also recalls issues we have seen in previous weeks, particularly the challenges of balancing academic interests in investigation and preservation of archaeological sites and the economic interests of local people and descendant communities.

Francisco, left, José, and María Belén Méndez talking about their micro-saving group. Photo by Takeshi Inomata.

Francisco, left, José, and María Belén Méndez talking about their micro-saving group. Photo by Takeshi Inomata.

As you read, think about the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project in the historical context of Maya archaeological and the social context of contemporary Guatemala. How does this article recall our previous readings and discussions about "Big Digs," education about the Maya past, critiques of tourism and development, or issues with archaeological looting?

Background image: Excavations in the royal palace of Ceibal, carried out by members of the community of Las Pozas and American archaeologists. Photo by Takeshi Inomata.

5. Optional: Iyaxel Ixkan Anastasia Cojtí Ren, "The Experience of a Mayan Student"

As Oswaldo Chinchilla noted in his chapter on the history of Guatemalan archaeology, indigenous peoples have been left out of the study of the past until recently. We have seen this in previous reaadings ourselves, not only in critiques of that exclusion, but also in how it can change, especially the central role of indigenous scholars and linguists in the creation of the Kaqchikel stela at Iximché. In this short chapter, Iyaxel Cojtí Ren—one of the experts consulted on the Iximché stela (whom some of you might also recognize from the Maya at the Playa conference in October)—describes her experience as a Maya-K'iche' archaeologist. Since writing this chapter, Cojtí Ren has received her PhD in anthropology from Vanderbilt University and is currently a post-doctoral fellow at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC. Beginning next year, she will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Texas in Austin.

Her chapter describes her personal challenges navigating an often exclusionary education system in Guatemala, but also provides her perspective on the history of Guatemalan archaeology. She also highlights possibility for further incorporation of indigenous people into archaeological practice and ways to improve the field as a whole.

Access a PDF of Iyaxel Ixkan Anastasia Cojtí Ren's, "The Experience of a Mayan Student" here.

As you read Cojtí-Ren's chapter, consider how it bridges Chinchilla's history of archaeology and MacLellan and colleagues' recognition of the mutliple roles archaeology can (and perhaps should) fill beyond scholarship and tourism. Think too about the common thread in these pieces—the way that foreign (especially American) academia still dominates Guatemalan archaeology. Many projects are still funded by external money, relationships wax and wane with field seasons (which often correspond to US academic calendars), and success in Guatemala is better ensured by an advanced degree from a foreign institution. Does the possibility to change those systems exist? What might it look like?

Background image: Iyaxel Cojtí Ren. Source: https://www.goafar.org/conference-directory/2020/2/5/iyaxel-cojti-ren

4. Optional: Bárbara Arroyo, "Juan Pedro Laporte (1945-2010)" (in Spanish)

Juan Pedro Laporte was an incredibly influential figure in Guatemalan archaeology. He began working with the Tikal Project, the National Museum, and the excavations at Kaminaljuyú as a high school student, completed his bachelor's degree at the University of Arizona, his licenciatura and master's degrees at the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México, and his PhD at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and eventually returned to Guatemala to head the newly formed program in archaeology at the Universidad de San Carlos.

Laporte produced a wealth of information about Guatemala's ancient past, developed strong relationships with local communities in the Peten (including the creation of regional museum in the town of Dolores), and trained multiple generations of professional archaeologists in Guatemala. He authored several books and was also one of the founders of the annual Symposium of Archaeological Investigations in Guatemala. Until his death, Laporte was the director of the Arcaheological Atlas of Guatemala Project, which identified, surveyed and mapped, and catalogued archaeological sites throughout Guatemala.

Access a PDF of Bárbara Arroyo's obiturary, "Juan Pedro Laporte (1945-2010)," here.

Background image: Juan Pedro Laporte. Source: Bárbara Arroyo, "Juan Pedro Laporte (1945-2010)," Journal de la Sociéte des américanistes, 96, no. 2 (2010): 293-296.

5. Optional: Pia Flores, "Dos arqueólogas: Nuestro trabajo es mas que lo que salió en NatGeo (y no es para el turismo)" (in Spanish)

This article waas written in response to the National Geographic episode about the PACUNAM lidar project that we watched in Week 2. In it, Flores critiques the episode's narrative for focusing on foreign, male archaeologists and for its sensationalism in making fast, big discoveries seem like the goal of archaeology. She does so by highlighting the work of the archaeological project at the site of El Tintal, co-directed by two Guatemalan women: Mary Jana Acuña and Varinia Matute.

Access Pia Flores's, "Dos arqueólogas: Nuestro trabajo es mas que lo que salió en NatGeo (y no es para el turismo)" here (in Spanish).

In this interview with Acuña and Matute, topics range from the importance of the local component of archaeology (even in the time of lidar), the "Indiana Jones" stereotype, the role of tourism in archaeology, and the Tintal project itself.

Background image: Members of the Proyecto Arqueológico El Tintal, including co-directors Mary Jane Acuña and Varinia Matute (center). Photo by PAET.

Jessica MacLellan

Dr. Jessica MacLellan is an anthropological archaeologist, with a particular focus on the role of household ritual in the development of ancient Maya society. She received her bachelor's degree from Boston University and her master's and doctorate degree from the University of Arizona, where research was supported by the Jacob K. Javits foundation and the National Science Foundation. She previously held a junior fellowship at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC and is currently an ACLS Emerging Voices Fellow in anthropology at UCLA. She will begin a postdoctoral fellowship with the Smithsonian Institution in 2021.

As you know from her article, Jess has been a member of the Ceibal-Petexbatun Archaeological Project (since 2012), where she investigated early households and began a public outreach program to bring a greater understanding of archaeology and the ancient Maya to schools in the communities around Ceibal. She is also interested in archaeological outreach and education in the US.

Alejandra Roche Recinos

Alejandra Roche Recinos is an anthropological archaeologist who specializes in the study of stone tool technologies and economies, especially among the ancient Maya. She received her bachelor's and licenciatura degrees from the Universidad del Valle in Guatemala, her master's degree from Brown University, and will receive her Ph.D. from Brown in 2021, where her work has been supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. She is currently a junior fellow at Dumbarton Oaks.

Although Alejandra's dissertation work focuses on market systems and regional exchange networks in the kingdom of Piedras Negras, she has served as an archaeologist and lithics analyst at numerous other sites in Guatemala, including La Corona, Kaminaljuyú, and Tak'alik Ab'aj. Since 2018, she has been working at subsidiary centers of Piedras Negras in Mexico as part of the Proyecto Arqueológico Budsiljá-Chocoljá.

Breakout Group Activity: Peer Review workshops for Shorthand Rough Drafts

Before today's synchronous class meeting, you will have been assigned and reviewed a classmate's Shorthand rough draft. During today's Breakout Group sessions, you will have the opportunity to discuss your feedback and ask questions of your peer reviewer.

As a reminder, your written evaluation of your partner's Shorthand rough draft should address any orthographic or grammatical errors and include your responses to the following questions:

1. Does the page tell a compelling story? Are the components of that story organized effectively and articulated clearly?

2. Are there any perspectives/arguments/themes/knowledge that are missing and should be addressed? (Please be specific about what they are and why they are important).

3. How well does the evidence from relevant sources support the claims made on the page? How is that evidence used (e.g., paraphrasing, quotes, photos/videos, etc.). Are the page author’s conclusions or stance on the topic warranted given the evidence? Why or why not? Is the author’s interpretation of the source materials straightforward or is it in any way misleading?

4. Discuss at least one specific strength and one specific weakness of the page.

5. What specific revisions would you suggest to improve the page?

After the Breakout Group session, we will reconvene as a group to discuss any page highlights, lingering questions, etc.