October 13: Big Digs

Who are some of the key people and institutions in the development of the discipline of Maya archaeology? How do intellectual genealogies (professors-students-partners-etc.) shape the practices, methodologies, and theories of Maya archaeology? What are some of the driving forces behind funding support for Maya research?

October 13: Agenda

In this week's synchronous class meeting we will:

1. Begin with a conversation/Q&A session with our invited speaker, Professor Stephen Houston of Brown University (don't forget to post questions for Professor Houston to the dedicated Canvas questions forum by 12 PM!)

2. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to also post to the Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!)

3. Discuss your Shorthand practice pages

Readings for Discussion

This week's readings will introduce you to a number of important people, places, and projects in the field of Maya archaeology. You will also be exposed to a variety of key forms of knowledge production: archaeological excavation techniques, varied forms and venues for publication, and different degrees of collaboration among experts, amateurs, locals, and foreigners, to name a few. Across all of the resources below (and indeed throughout the rest of the quarter), be mindful of how ideas about the past have changed or developed over time in response to technological improvements; shifting political, ethical, or economic concerns; and social as well as intellectual relationships.

1. Stephen L. Black, “The Carnegie Uaxactun Project and the Development of Maya Archaeology”

Founded in 1902 by Andrew Carnegie with an initial endowment of $10 million, the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW) provided (and, in some disciplines, continues to provide) funding for scientific discoveries. Between 1914 and 1958, the CIW sponsored a range of projects to study the ancient and mid-twentieth century Maya people of southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and western Honduras and El Salvador. At the time, no university or other research program could match the monetary and human resources of the CIW. The CIW Maya program, whic produced more than 300 publications, has been called "the most significant anthropological project ever undertaken to examine a single anthropological or archaeological region."

One of the first major archaeological excavations sponsored by the CIW in the Maya area was at the site of Uaxactun, in northern Guatemala, between 1924-1937. As you will gather from this week's readings, many of the approaches still employed in Maya archaeology today are rooted in the work of the CIW Mayanists, among whom were not only archaeologists, but also ethnographers, linguists, historians, and other researchers (the University of Chicago's anthropologists, in fact, played an important role in ethnographic and linguistic research collaborations with the CIW). In Stephen Black's article, in particular, you will also see how institutional and personal connections—what he calls "the Uaxactun archaeological lineage"—established, spread, and maintained the traditions of the CIW. Uaxactun was also a key site in establishing the profound (and unexpected) time depth of Maya civlization.

Access a PDF of Stephen Black's "The Carnegie Uaxactun Project and the Development of Maya Archaeology" here.

There are a lot of names in Black's article—CIW and other archaeologists, archaeological sites, and US and Central American institutions. Many of these people and places will reappear in other materials assigned for this week and over the course of the quarter, becoming more and more familiar. As you read, keep your focus on Black's broader claims about how the CIW created long-lasting lineages and fieldwork traditions in Maya archaeology (rather than keeping track of particular individuals). For those of you who have experience in archaeological fieldwork, take a close look at the photographs of the CIW excavations at Uaxactun and Smith's instructions for how to excavate a temple (p. 269-279) —how would investigations like those of the E or A Group be undertaken in a different time (e.g., today) or place?

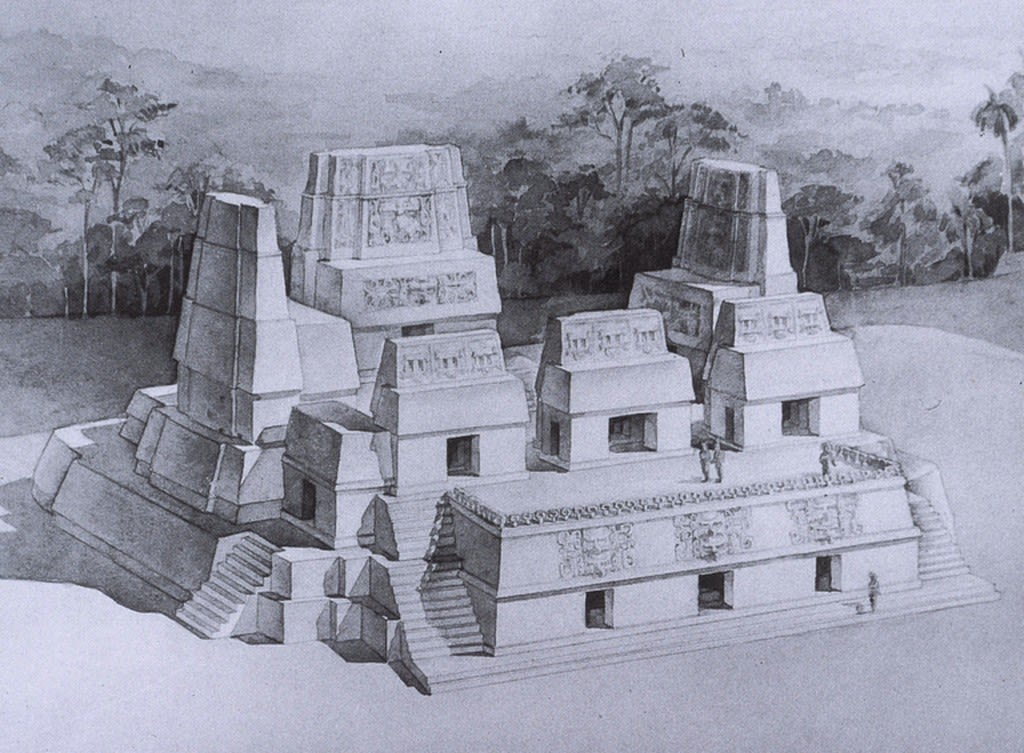

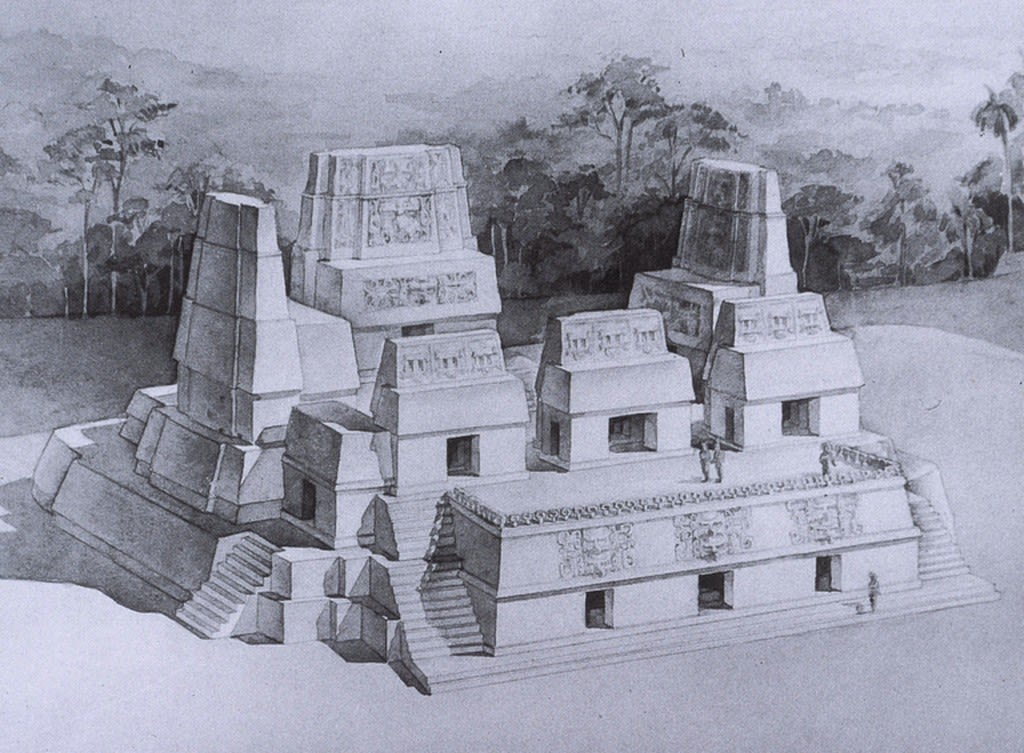

Group E (platform E-VII-sub) from Uaxactun. Reconstruction by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

Group E (platform E-VII-sub) from Uaxactun. Reconstruction by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

Structure A-V from Uaxactun. Reconstruction by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

Structure A-V from Uaxactun. Reconstruction by Tatiana Proskouriakoff.

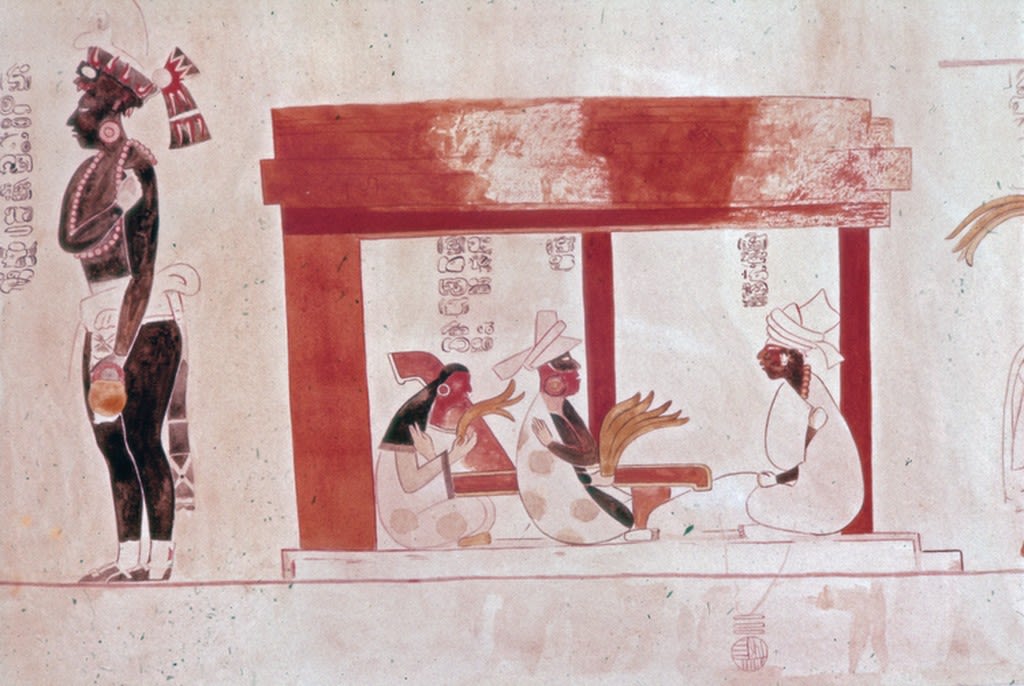

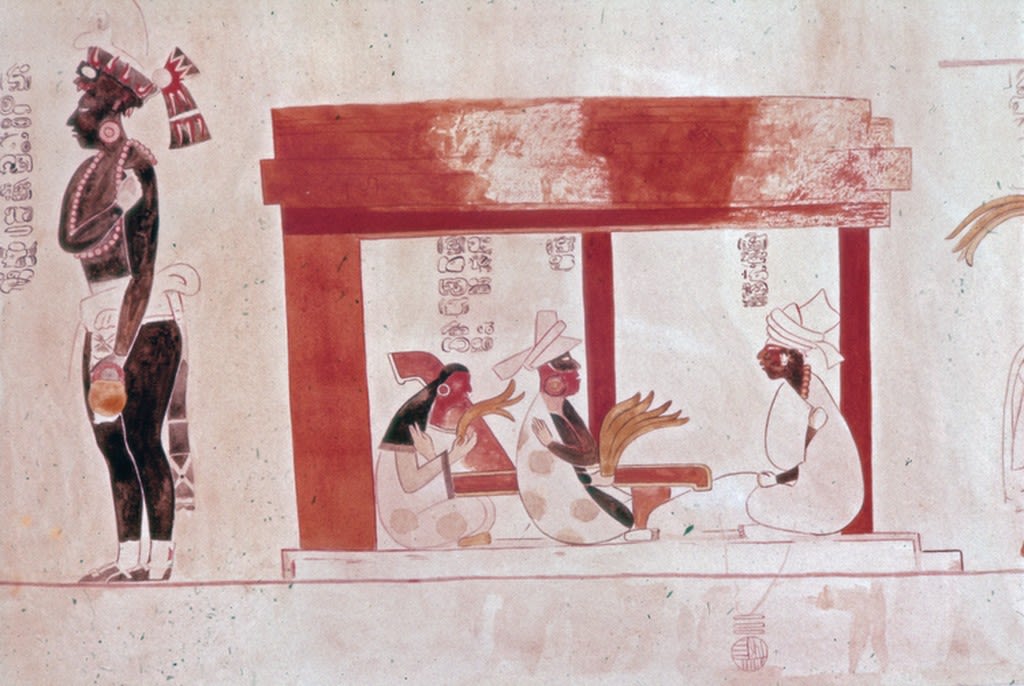

A (now-destroyed) fresco from Uaxactun Structure B-XIII. Reconstruction by Antonio Tejada.

A (now-destroyed) fresco from Uaxactun Structure B-XIII. Reconstruction by Antonio Tejada.

Edwin Shook documenting Cache 119 at Tikal

Edwin Shook documenting Cache 119 at Tikal

2. Edwin Shook (as recounted to Stephen Houston), "Recollections of a Carnegie Archaeologist"

Although Edwin (Ed) Shook appears only briefly in Stephen Black's article, Shook was a central member of the CIW team. Trained as an engineer, he began working at Uaxactun as a draftsman, drawing (or correcting) key plans and sections of excavations. Later, Shook worked as a principal archaeologist for other CIW projects, including at Kaminaljuy in Guatemala and at Mayapan in Mexico. He is best known, however, for serving as the field director for the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania's Tikal Project from 1956-1962.

Access Edwin Shook's "Recollections of a Carnegie Archaeologist" here.

In this reading, Shook provides a complement to Black's article, fleshing out the history of the CIW with more personal stories and recollections (including about particular members of the CIW team). Among the "little juicy tidbits" (as he calls them) and the "tricks" and rituals Shook remembers, note also his specific contributions to archaeological methods and documentation techniques and the overarching aims, successes, and failures of the Carnegie investigations.

3. Fox Movietone News, “Mecca of the Americas, Chichen Itza” (1931)

As Ed Shook described in his "Recollections," Sylvanus Morley was "like a little hurricane," "one of those bubbling, enthusiastic people," someone who "had the ability to put you on fire, make you squirm with intellectual excitement." Morley understood support for Maya archaeology to require both academic interest and excitement among people outside the field (a view that still holds true—recall the Science article and National Geographic episode from October 6).

In the clip below, you'll get a sense of Sylvanus Morley's showmanship, occasional exaggerations, and flair for adjectives. Be aware that much (if not most) of the information and interpretations in the video are now outdated. As you watch, note the differences between the work carried out at Chichen Itza on behalf of the CIW and the work at Uaxactun (e.g., the emphasis on reconstruction vs. excavation, the names given to structures such as "Temple of the Warriors" vs. Group A-V, etc.).

4. Optional: Franz Boas, "Scientists as Spies"

Sylvanus Morley, in addition to directing projects for the CIW, also worked as a spy for the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War I. During his travels to visit archaeological sites and conduct surveys throughout Central America, Morley was simultaneously tasked with identifying possible German agents and hunting for covert German shortwave broadcast stations and hidden submarine bases. According to anthropologist David Price, historians have deemed Morley "arguably the best secret agent the United States produced during World War I."

In fact, Morley was only one of many American archaeologists who used their profession as a cover for intelligence-gathering activities. In 1919, Franz Boas (the "father" of academic anthropology in the United States), wrote this letter to the editor of The Nation, in which he criticized four unnamed archaeologists (now thought to include Morley) for "prostituting science" and threatening future research. Boas was censured by the American Anthropological Association for his letter (by a committee that included several anthropologists working as spies) in a decision that was not reversed until 2004.

Access Boas's letter, "Scientists as Spies" here

5. William R. Fowler, Jr. and Stephen D. Houston, “Excavations at Tikal, Guatemala: The Work of William R. Coe"

The University of Pennslyvania's Tikal Project ran for 14 consecutive years (1956-1970), operating two seasons per year. It was a massive undertaking, involving not only the excavation and restoration of Tikal's architecture, but also the construction of full-time camps and villages for archaeologists and local excavators and their families, as well as the development of infrastructure (roads, airstrips, hotels) to transform Tikal into a tourist destination once research was completed.

As noted above, the project began with Ed Shook as its director. Despite having decades of field experience, Shook had never been academically trained as an archaeologist—a fact that one of his principal archaeologists, William (Bill) Coe, found unacceptable. (Bill Coe, by the way, was the brother of Michael D. Coe). Coe and Shook argued over the project's archaeological methods and practices at Tikal, such as the scales at which drawing should be made (1:50, in the CIW tradition, or 1:20, where more details could be seen?) or the degree to which later phases of buildings should be removed to examine earlier ones. Tensions between Shook and Coe grew to the point that the University Museum sent down its associate director, Alfred Kidder II (the son of the Alfred Kidder who ran the CIW division of historical research), to mediate between them. In 1962, the University Museum "retired" Shook as director. Coe took his place in 1963 with Aubrey Trik, an architect in charge of conseration, then became the official head of the project in 1964.

Optional: Tikal Project - 1959 #1 (Scenes from the 1959 field season, including excavations in the Great Plaza)

Coe was widely regarded as a brilliant and talented archaeologist: a meticulous excavator and excellent draftsman with an intuitive grasp of contexts and constructions. Perhaps his greatest achievement is the monograph reviewed in this week's reading by William Fowler and Stephen Houston. Across six volumes, remarkable for their details, Coe presents a coherent picture of the complicated archaeology carried out season after season in Group 5D-2, Tikal's Classic-period epicenter.

Access Fowler and Houston's “Excavations at Tikal, Guatemala: The Work of William R. Coe" here.

Reading Fowler and Houston's review will give you a sense not only of the volumes' contributions to Maya archaeology, but also their idiosyncrasies. As you read the review, think about how Coe chose to organize and convey archaeological data in his report, as well as how he describes the project's methodological approaches. Pay attention to Fowler and Houston's criticisms as well.

Coe's six-volume report is only one of an ambitious series of publications—39 volumes were planned in total. Eleven were published during fieldwork, but many were delayed by the high standards set by Coe (he also discouraged project members from publishing information anywhere else until their dedicated volume of the Tikal Reports was completed). A number of authors have died without completing their volumes.

Optional: If you are interested can access many volumes of the Tikal Reports (Coe's and others') via the HathiTrust here (requires UChicago login).

6. Lizzie Wade, "The Believer: How a Mormon lawyer transformed Mesoamerican archaeology—and ended up losing his faith”

This article focuses on the history of the New World Archaeological Foundation and its founder, a Mormon lawyer and archaeologist named Thomas Stuart Ferguson. In 1830, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), Joseph Smith, published the Book of Mormon. According to Smith, the Book of Mormon was translated from golden plates inscribed by an ancient people called the Nephrites. After the publication of Stephens and Catherwood's Incidents of Travel, many Mormons (including Smith himself) thought the ruins described by Stephens were the works of the Nephrites. In the 1950s, Ferguson, who had studied Mesoamerican archaeology as an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, obtained LDS funding for archaeological excavations to explore the origins of Mesoamerican civilizations in the hopes of finding evidence to support the Book of Mormon).

Access Lizzie Wade's "The Believer: How a Mormon lawyer transformed Mesoamerican archaeology—and ended up losing his faith” here.

Now more distanced from its roots in LDS beliefs, the New World Archaeological Foundation (NWAF) continues to provide support for archaeological research in Mesoamerica. There are also robust programs and exceptional scholars in Mesoamerican anthropology and linguistics at Brigham Young University (a private research institution owned by the LDS Church). As you read Wade's article, think about how/whether the interests motivating funding from and the results achieved by the NWAF are similar to or different from other institutions, such as the CIW.

7. VICE News, “Mayan Ruins in Guatemala Could Become a U.S.-Funded Tourist Attraction”

This recent video from VICE News ties together various threads from the readings above: the impacts of large, well-funded, and long-lasting foreign projects in Guatemala; the complex relationships between archaeologists and people who live at or near archaeological sites; questions over whether ruins should be preserved for the future or made available for tourism in the present; issues with timely publication; and even the LDS Church's continued interests in Mesoamerican archaeology.

8. Brown University, "El Zotz masks yield insights into Maya beliefs"

Invited Guest: Professor Stephen Houston

By now, you should be familiar with some of the varied works of our guest this week, Professor Stephen Houston (you also read the introduction to his book on the Classic Maya with Takeshi Inomata last week). Although most scholars either recover ancient art and artifacts as archaeologists or study those materials as epigraphers and/or art historians, Houston's expertise encompasses both stages of research. He has directed several major excavation projects at sites such as Piedras Negras and El Zotz in Guatemala, in addition to excavations and documentation at sites including Bonampak, Caracol, and Dos Pilas. Houston has written over thirty books and hundreds of articles and chapters, on topics ranging from kingship and court systems to ancient conceptions of body, color, materiality, and dress; writing systems, decipherment, and epigraphy; architecture, urbanism, and warfare; among others.

The first video at right is from Houston's project at the site of Piedras Negras, Guatemala (apologies for the low quality - it was recorded by KBYU television in 1999). As you'll hear in Houston's narration, Piedras Negras had also been the focus of a University of Pennsylvania project in the 1930s. Note how Houston calls attention to some of the "clean-up" work that was required after the UPenn project (much like the criticisms leveled against the CIW work at Uaxactun).

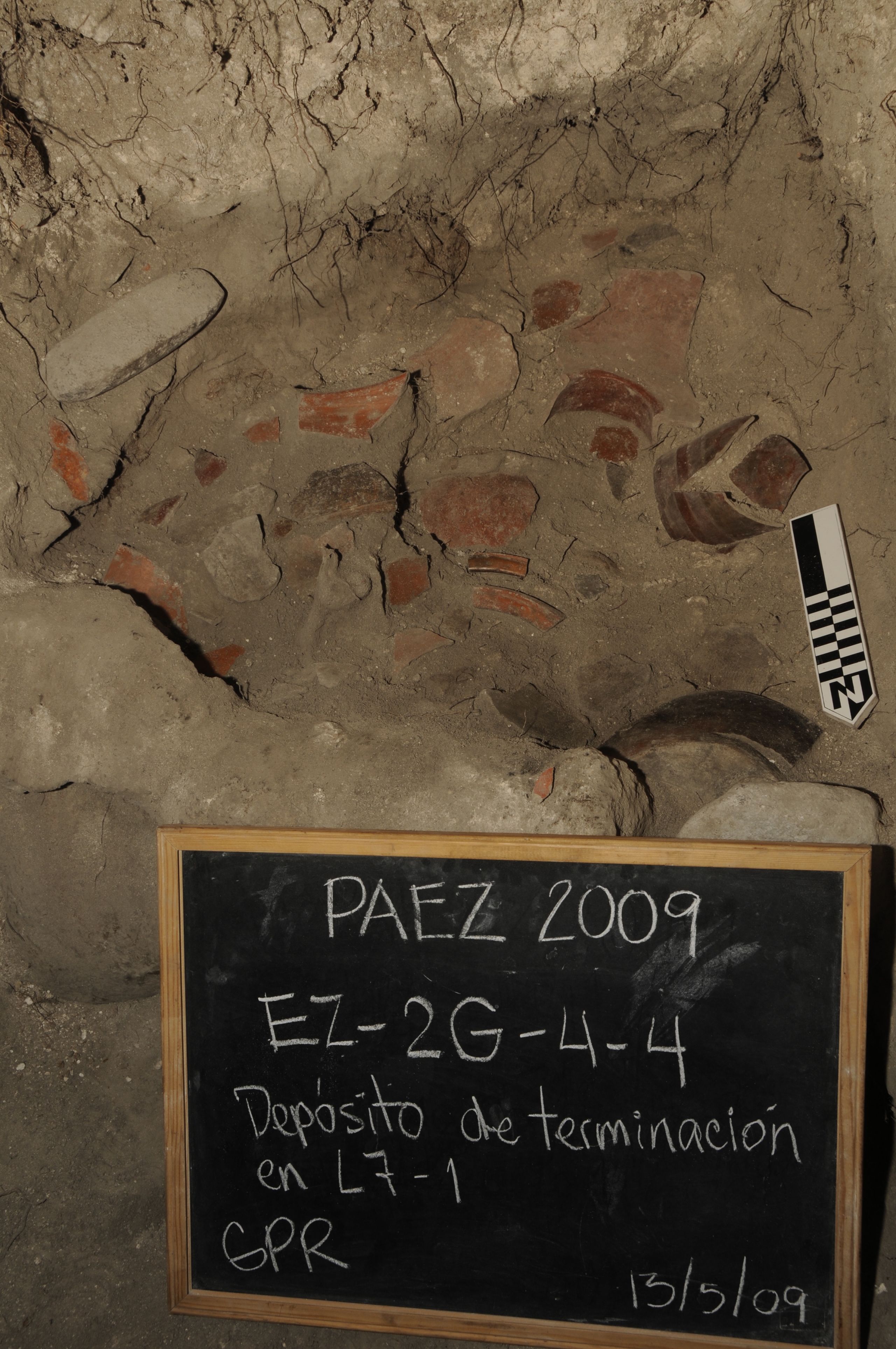

The second video will introduce you to one of Houston's recent remarkable finds (there have been many others!). Beginning in 2006, Houston directed excavations at the site of El Zotz, located in Guatemala's Department of Peten. In 2009, at a hilltop settlement known as El Diablo, the project uncovered a small Early Classic (c. AD 400) temple, completely encased within later funerary monuments. Known as the Temple of the Night Sun, the structure has an elaborate façade covered in polychrome, modeled stucco that depicts both gods and local rulers. In 2010, Houston found the intact tomb of the first king of the El Zotz dynasty, directly beneath the Temple of the Night Sun. I was working at El Diablo that year (as a first-year graduate student) and excavated the tomb along with Houston, Guatemalan archaeologist Edwin Román, and Thomas Garrison (then a post-doc at Brown, now a professor at the Unviersity of Texas).

The El Diablo tomb was a major discovery for many reasons. The early date of the El Diablo tomb made it a rare find. As the burial of the city's dynastic founder, moreover, it was a spectacularly rich tomb, containing ceramic vessels of various kinds, masks carved from jade, and even the remains of six sacrificed children. Undisturbed for over 1600 years, objects that are often lost to the elements were preserved in the enclosed space (e.g., fragments of textiles, vessels made out of gourds covered in painted stucco).

Optional: If you are interested, you can flip through our publication of the El Diablo tomb excavations here.

Professor Houston at Piedras Negras Structure O-13

Professor Houston at Piedras Negras Structure O-13

A painted ceramic vessel with a flying macaw motif from the El Diablo tomb.

A painted ceramic vessel with a flying macaw motif from the El Diablo tomb.

A fragment of a stucco vessel in the shape of an aquatic bird from the El Diablo tomb (another fragment of a stucco fish in the bird's beak was found as well).

A fragment of a stucco vessel in the shape of an aquatic bird from the El Diablo tomb (another fragment of a stucco fish in the bird's beak was found as well).

A jade earspool from the El Diablo tomb.

A jade earspool from the El Diablo tomb.

9. Optional: Marshall Joseph Becker, “Priests, Peasants, and Ceremonial Centers: The Intellectual History of a Model”

This week's required readings have focused on the methods, practices, and intellectual lineages of Maya archaeology's "Big Digs." Major institutions like the CIW, Harvard University, or the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania not only established standards for how fieldwork would be carried out and how projects would be organized for decades, but they also decided which interpretations about the ancient Maya were considered valid.

This optional chapter is itself now almost half a century old, but it provides an in-depth intellectual history of ideas about ancient Maya civilization, starting in the mid-nineteenth century. Becker describes in detail the full range of theories about Maya society: from a traditional view of social class structure (complex cities and numerous classes), to one focused on ceremonial centers with priests aand peasants, to a model based on egalitarian towns with rotating office holders. Becker also relates how Maya archaeology shifted from the dominance of the CIW to university-centered investigations.

Access Becker's “Priests, Peasants, and Ceremonial Centers: The Intellectual History of a Model” here.

10. Optional: Sarah E. Newman, “Rubbish, Reuse, and Ritual at the Ancient Maya Site of El Zotz, Guatemala”

I'm including this article of mine as an optional reading for this week because the beginning of the paper discusses how specific ideas are invented/proposed, taken up, refined, and reifed in archaeology. The article traces how the concept of "termination" (the notion that the ancient Maya performed rituals to "kill" enlivened objects and architecture) began as a concept proposed by Bill Coe atPiedras Negras, was then extended to describe a type of archaeological context at other sites, and eventually became something archaeologists now supposedly recognize in the ground. If you're interested, focus on the "Introduction" and "Termination Ritual as Category and Context" sections (p. 807-814).

Access my "Rubbish, Reuse, and Ritual at the Ancient Maya Site of El Zotz, Guatemala" here.