September 29: Introduction

Personal introductions; course overview and requirements; review of themes and key questions

September 29: Agenda

Welcome to the first session of "Making the Maya World"!

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Introduce ourselves to one another

2. Cover the basic goals, structure, requirements, and schedule of the course

3. Discuss a short reading (Jorge Luis Borges's “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”)

4. Complete a Breakout Group "Quick-Fire Bibliography" challenge (an initial foray into studying Maya archaeology and (its) history)

About Me

I am an anthropologist and archaeologist. I've been researching, writing, and conducting fieldwork in Mesoamerica (in Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras), with a particular focus on the ancient Maya, since 2006.

My research explores many different forms of human interactions with ancient environments. For example, I'm currently writing a book about the changing nature of waste in Mesoamerica, which shows how things archaeologists have long considered to be ancient trash—broken pots, bone fragments, worn-out tools, or crafting debris—may have held different meanings in the past. The long-term, cross-cultural perspective of the book shows how the idea that "waste" is a self-evident and universal concept is not only anachronistic, but actively limits our capacity for understanding the past.

I am also a zooarchaeologist, meaning I study animal bones recovered from multiple excavation projects in Guatemala and Mexico. I am interested in ancient Maya dietary, hunting, and game management practices and their ecological impacts, but also in the relationships between humans and animals in the past and in how knowledge about the natural world was generated and expressed in the past.

Finally, I co-direct two ongoing field projects. One focuses on the site of Topoxté, in the Petén region of northern Guatemala, where a series of small islands were abandoned in the ninth century AD and later reoccupied by migrants from the northern Yucatan peninsula in Mexico around AD 1200. Our project seeks to understand the shape and composition of this post-collapse city, by asking a range of questions: Why did migrating Maya choose to reform and reconstitute urbanism, literally in the shadow of failed centers? How did people in the past recognize, reuse, and remake the monumental interventions of their predecessors in the landscape?

I also co-direct the Petra Terraces Archaeological Project in Jordan, a collaborative effort with Brown University and the University of Padua to study the natural resources, human interventions, and agricultural residues of semi-arid environments in southern Jordan. The cross-cultural (and cross-climatic) comparisons between Topoxté and Petra provide a testing ground to develop and refine methodologies for documenting and dating ancient agricultural and hydrological terracing, as well as an opportunity to explore how anthropogenic landscape modifications—some still in use by modern farmers—endure across environmental change, collapse, and abandonment.

If you are interested in finding out more about any of these projects, most of my publications can be found here.

Reading for Discussion

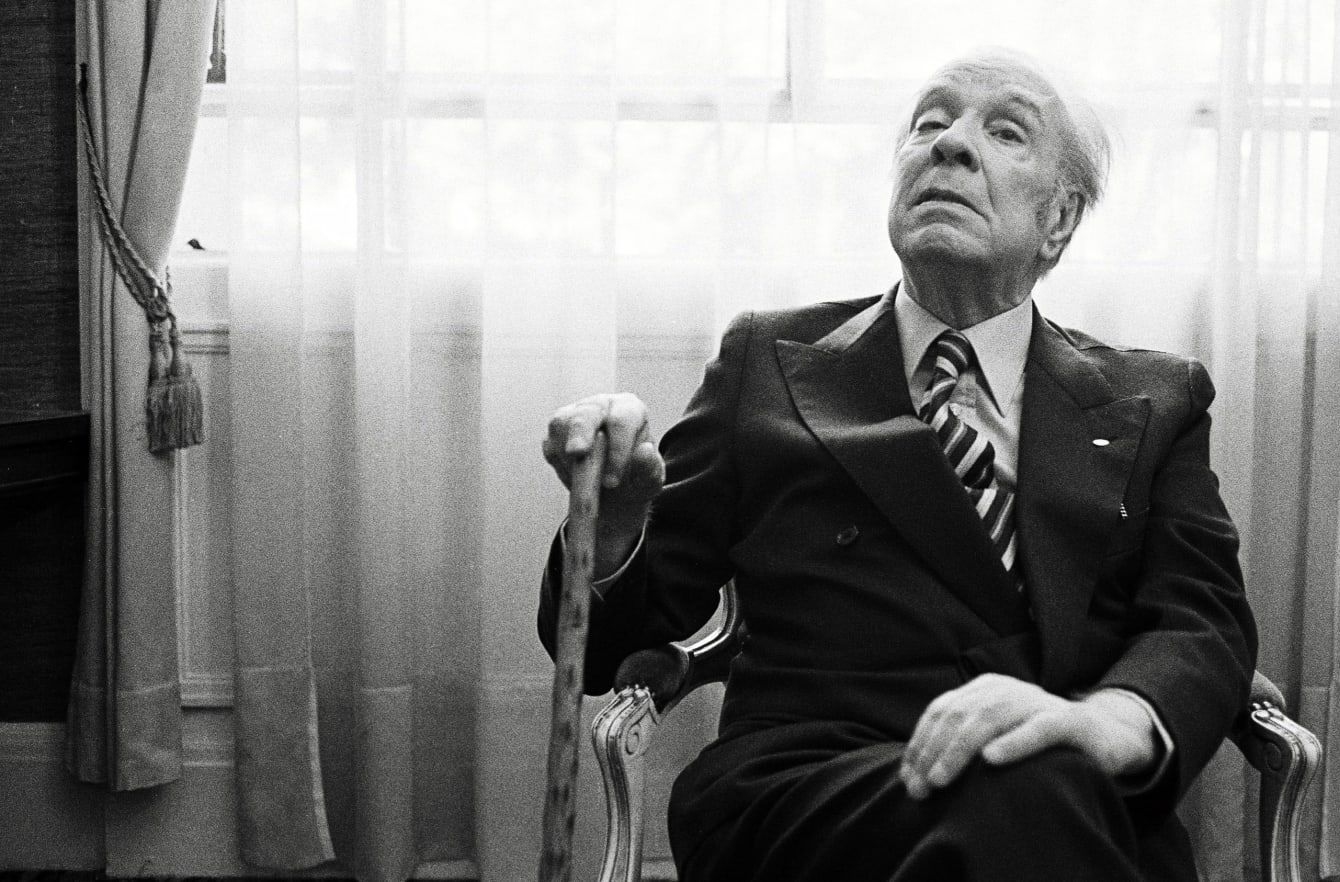

The only reading for this week is a short fictional story by the Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges.

Access a PDF of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" here or via the course Canvas module for September 29.

Borges is known for creating imaginary and symbolic worlds that play with the ideas of ancient and modern philsophers. He often takes a specific hypothesis to it's most extreme (but still logical) consequences, forcing us to ask ourselves what kinds of worlds would exist if the idea underlying it were true. Borges has said of his own work that it has two tendencies: "one to esteem religious and philosophical ideas for their aesthetic value, and even for what is magical or marvelous in their content...The other is to suppose in advance that the quantity of fables or metaphors of which man's imagination is capable is limited, but that this small number of inventions can be everything to everyone."

In Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, Borges imagines a planet where external reality is composed entirely of internal projections. In that world—known as Tlön—imagined objects are materialized as solid (if slightly deviating) copies of their idealized originals.

Borges explicitly addresses Tlön’s implications for archaeology. “The methodological fabrication of hrönir,” he writes, “has performed prodigious services for archaeologists. It has made possible the interrogation and even the modification of the past, which is now no less plastic and docile than the future.” Although "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" is obviously fictional, it prompts an uncomfortable reconsideration of very real epistemologies of archaeology that, like the Tlönian paradox mentioned in the story, have long troubled archaeologists.

As you read, ask yourself: What the implications of Borges's story for the modern discipline of archaeology? Prepare for our synchronous discussion by selecting one or two quotes or examples from Borges's story that you think are key to considering this question. If you wish, you may also point to specific examples of archaeological finds or interpretations that relate to this discussion.

Breakout Groups: Quick-Fire Bibliographies

In this Breakout Group activity, you will work with another student to produce a list of five resources on a particular topic, person, or place related to this course (Breakout Groups and topics will be assigned during our class session).

The goals of this activity are:

1. To become familiar with some of the key topics, people, and places we will cover this quarter

2. To highlight strategies for identifying appropriate sources, evaluating their relevance and usefulness, and building a cohesive bibliography

3. To start building a list of resources that can be drawn from in crafting individual Shorthand webpages for final projects

Bibliographies: 5 Tips for Getting Started

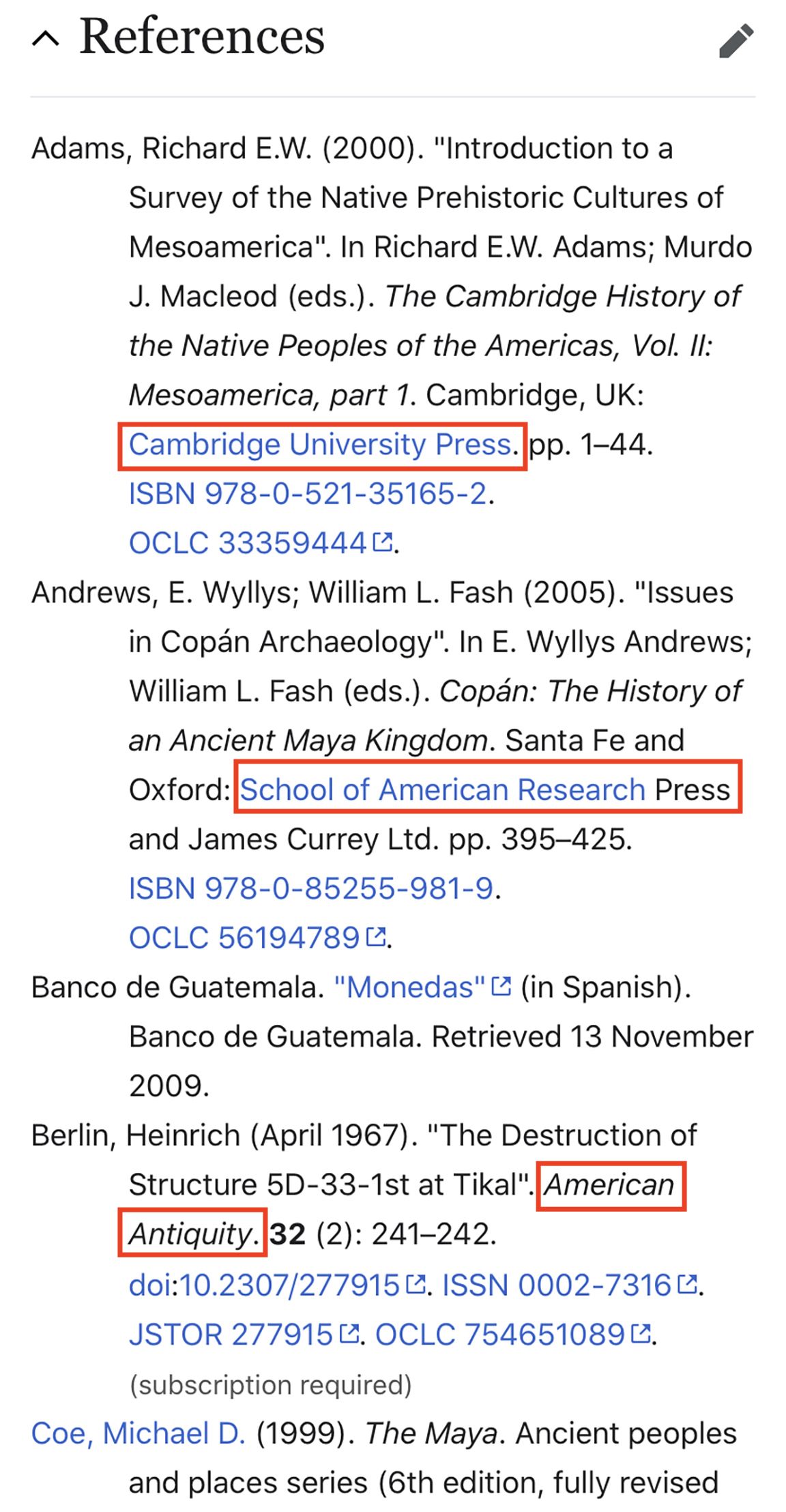

1. Wikipedia is a good place to start.

If you're completely unfamiliar with your assigned topic, person, or place, Wikipedia will likely provide a solid overview and a list of possible references at the bottom of the page. Look for links to books published by reputable presses (primarily university presses, but also Thames & Hudson, Routledge, Rowman & Littlefield, etc.).

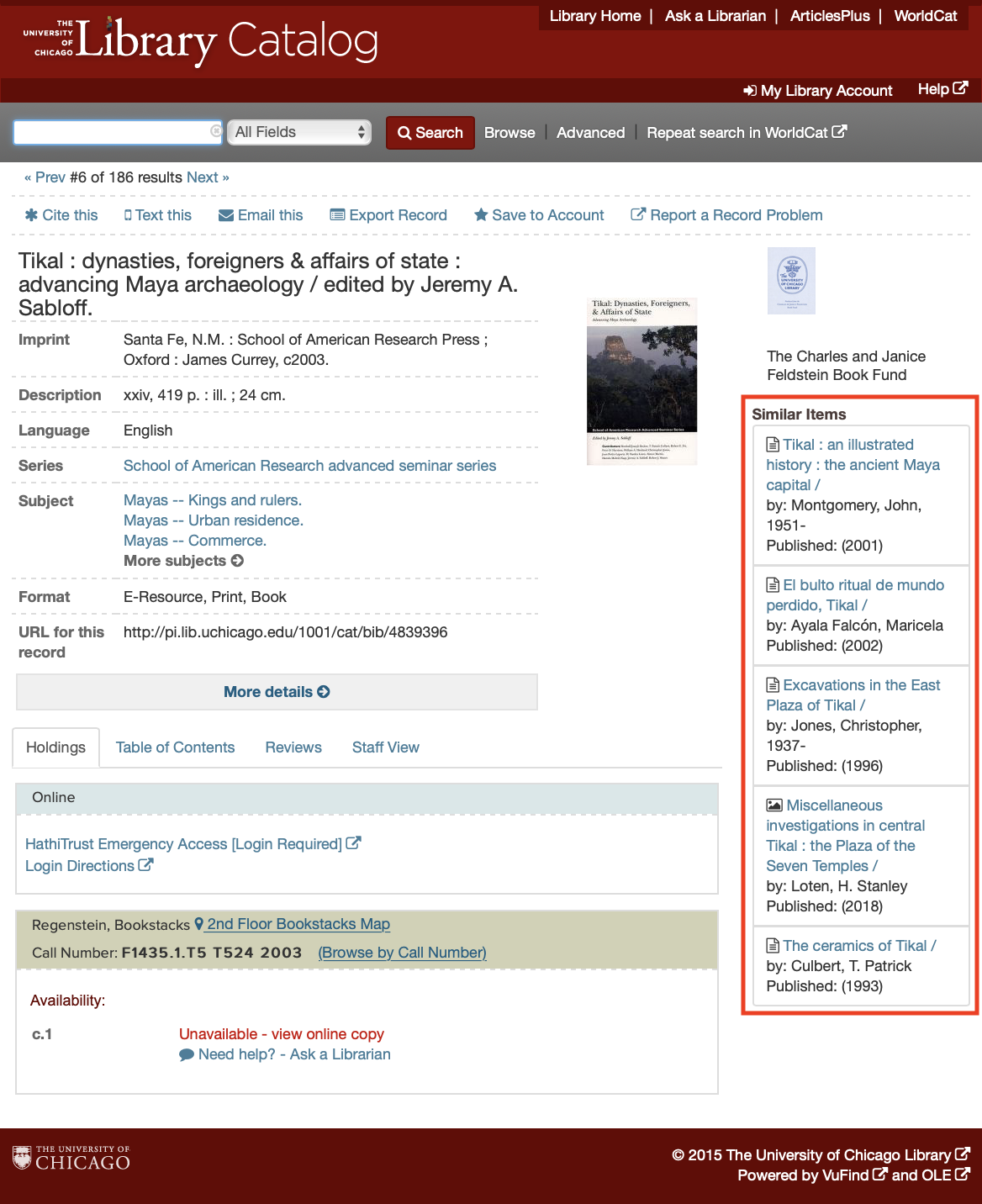

2. The university library's website can help you find related materials

If you find a relevant book, you can use the library's website to find specific suggestions for similar items (usually materials that share the same keywords). Those items will all be among UChicago's collections, making them likely to be peer-reviewed academic sources.

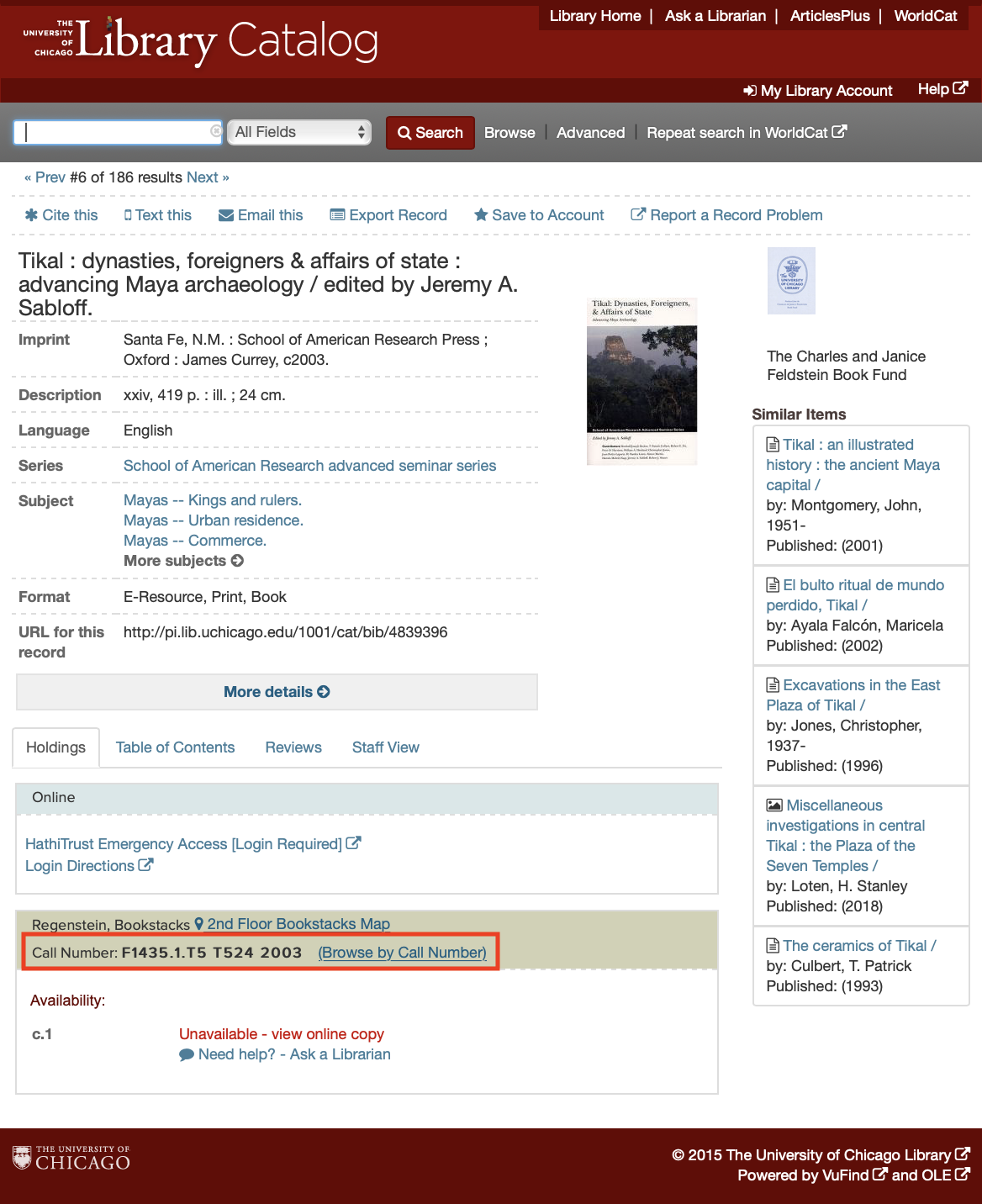

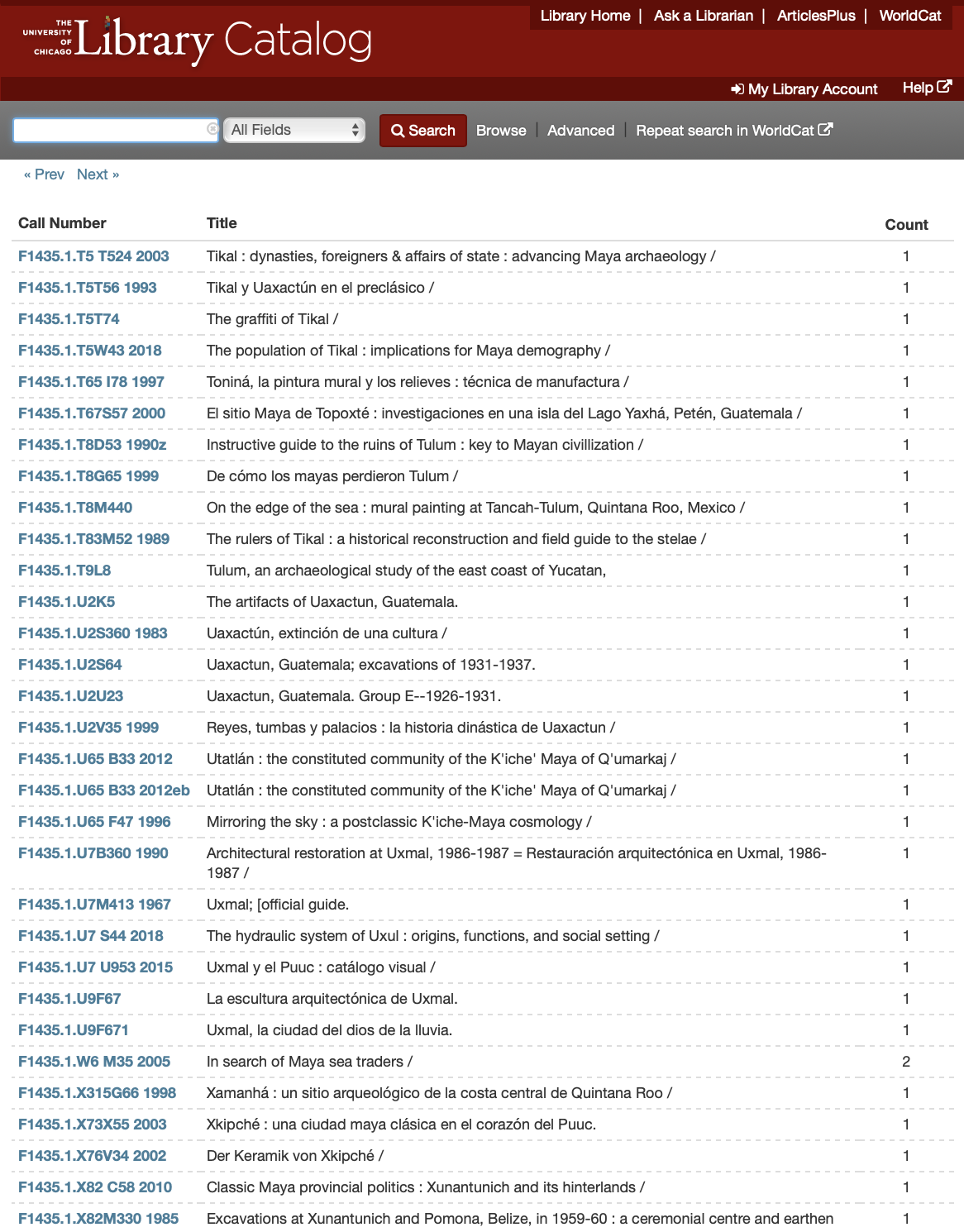

You can also find additional sources that are broadly related a particular item by browsing materials with similar call numbers (this is the digital equivalent of finding books on nearby shelves, so they will appear in alphabetical order).

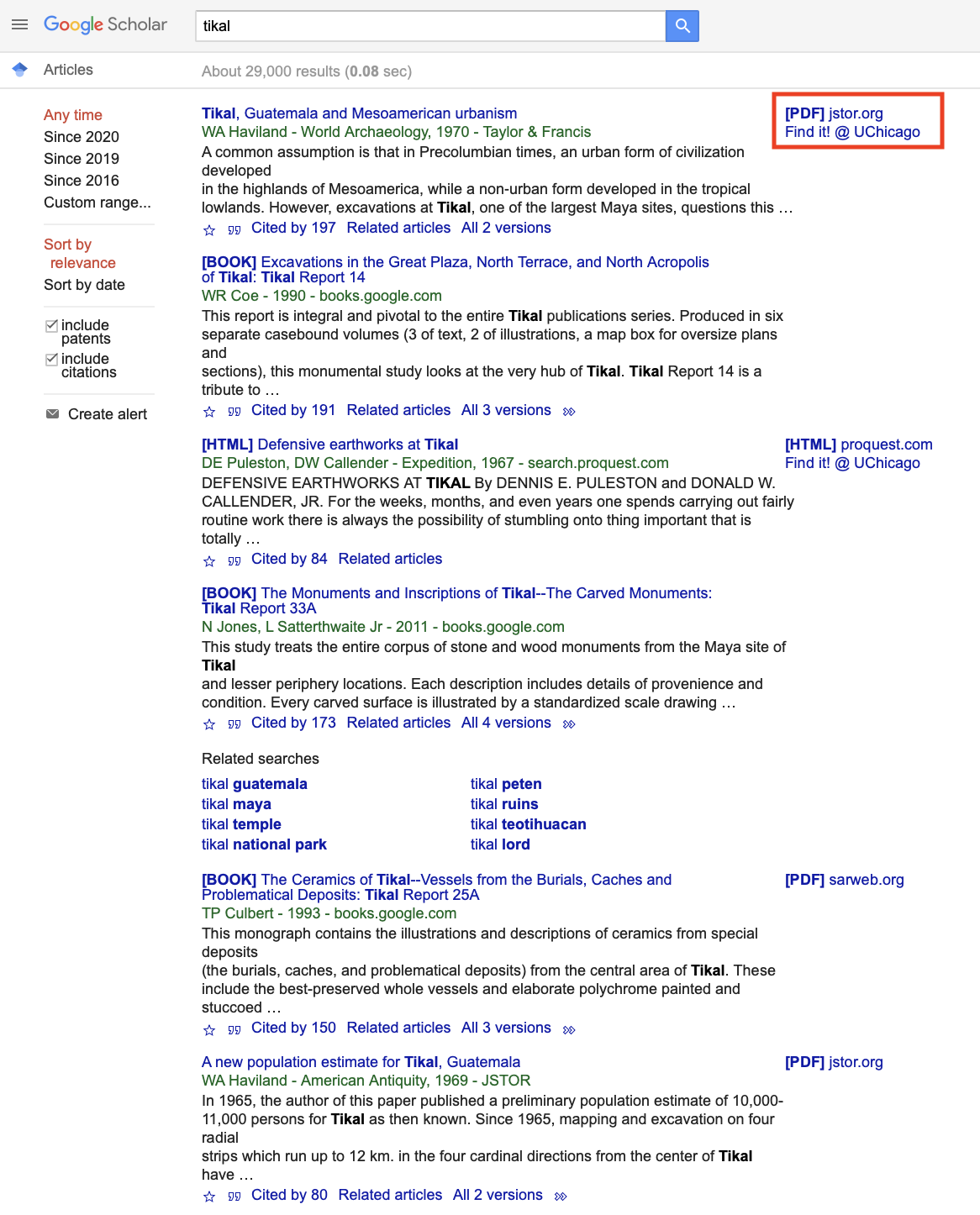

3. Google Scholar can link you to full-text journal articles and help you find new references in dialogue with work you are reading.

Simply entering your topic, person, or place in Google Scholar will lead you to relevant academic books and articles. You can set your preferences to add links to full-text journal articles available at the University of Chicago by following the guidelines here.

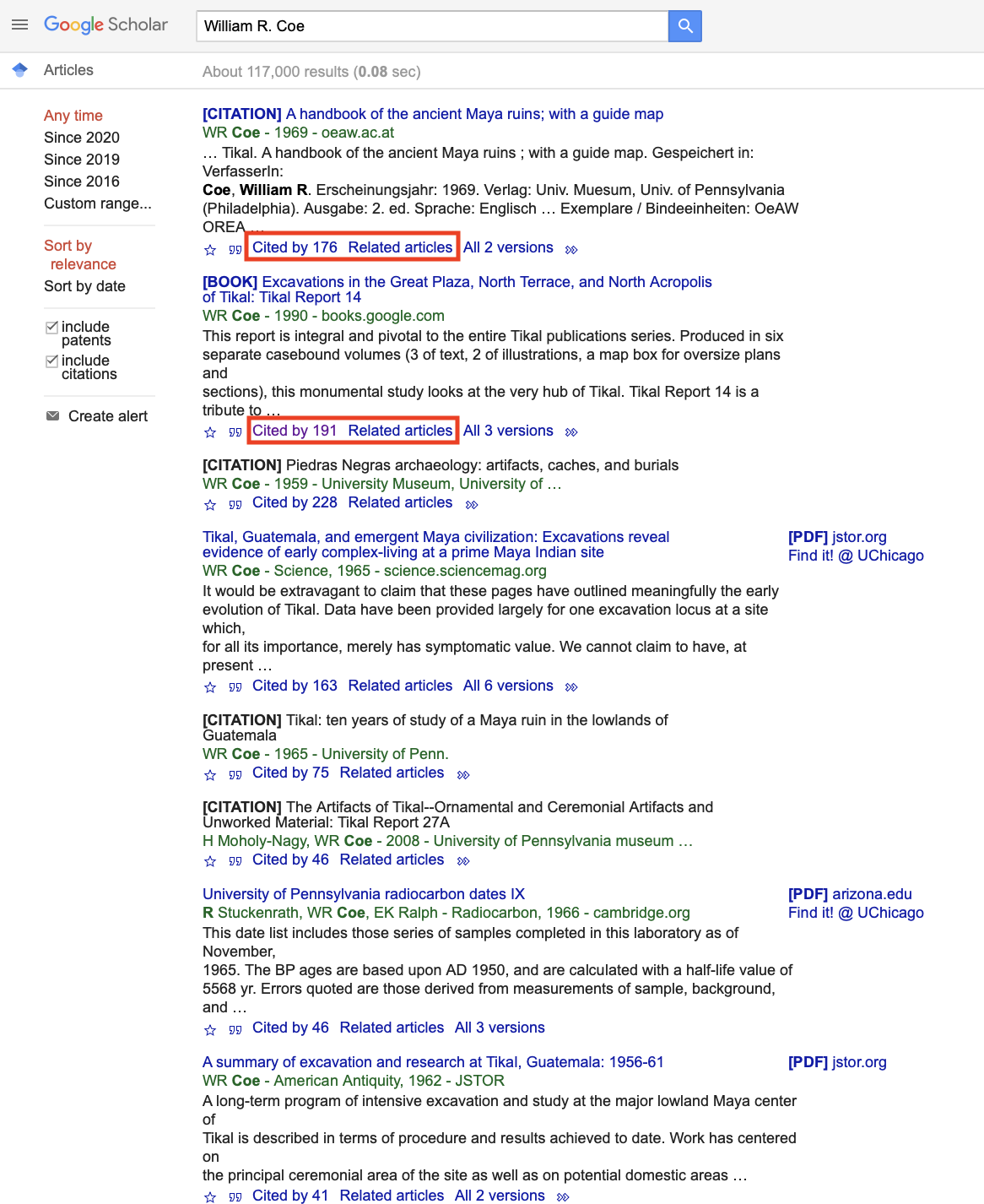

If you find an article or book that is relevant, but dated, you can search for that specific author or work to find other sources that have cited that person, article, chapter, or book (which may lead you to more recent publications by the same person or on the same topic). You can also search for new terms within books and articles citing a specific work.

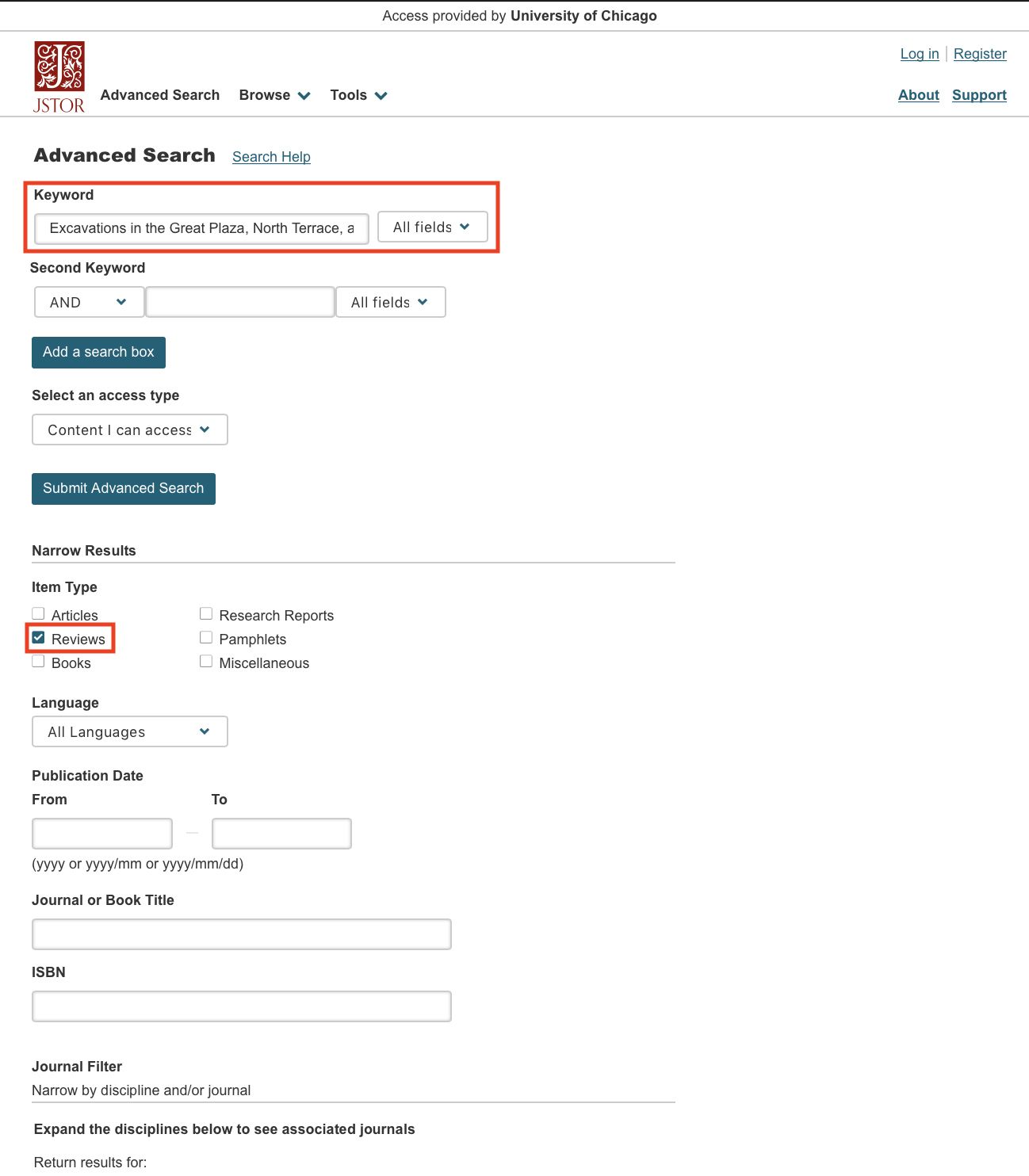

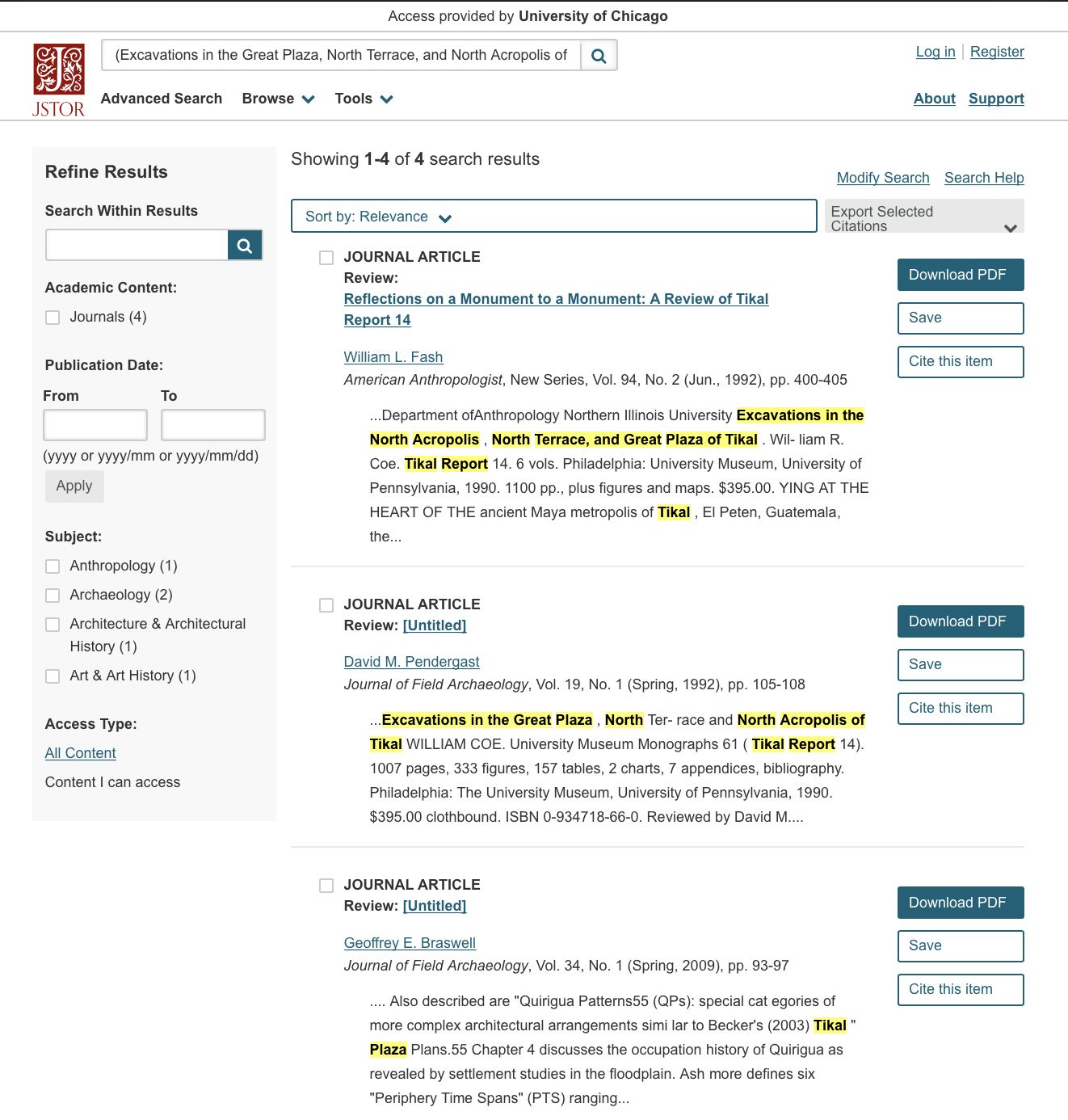

4. Reading a review can give you a quick(er) idea of whether a book or edited volume will be a useful resource.

If you want to assess whether a monograph or edited book will be helpful for your research, you can begin by reading a review or evaluaiton of the work. Good book reviews (usually by experts in the field) can be found in scholarly journals (many of which are collected in databases such as JSTOR) and in book review periodicals (e.g., the London Review of Books). In JSTOR, for example, you can conduct an advanced search for a book's title and narrow the results to reviews only.

5. Other resources may be available through digital libraries, such as the Internet Archive or HathiTrust

Digital libraries often contain digitized copies of older publications, which are particularly useful if you are studying the history of a particular topic or place or the works of an historical figure. You can login to the HathiTrust to access many full-text scans (and sometimes download them as PDFs). You can also access the Wayback Machine through the Internet Archive, which provides a library of billions of saved internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form.