October 6: Hidden Cities

How is Maya archaeology framed in terms of “discovery”? What are some of the ways in which the material culture, environments, and people encountered at Maya archaeological sites are described? How do narratives of discovery shape the questions that are asked (and who gets to ask them) about the Maya past and the way information is communicated to both scholarly and public audiences?

October 6: Agenda

In this week's synchronous class meeting, we will:

1. Discuss the week's readings and videos (don't forget to post to the week's Canvas discussion forum by 12 PM!)

2. Discuss your reviews of existing Shorthand pages

3. Complete a Breakout Group "Maya Ruins and the Passage of Time" activity (a "then-and-now" comparison of Maya archaeological sites inspired by the works of Frederick Catherwood and Jay Frogel)

Readings for Discussion

This week is both a literal and figurative orientation to the Maya world. Our discussions will be structured around the key questions posed for the week, those that come up in the dedicated Canvas discussion forum, and those that are specific to individual assigned materials (outlined below).

1. Houston and Inomata, "Introduction"

Begin with the introductory chapter written by two prominent Maya archaeologists, Stephen D. Houston (whom you will meet on October 13) and Takeshi Inomata. Houston and Inomata's chapter provides an overview of some of the basic facts, ideas, and terminology that we will encounter again and again in this course: "Maya" as a cultural and linguistic identity, the physical setting of the Maya world, a brief history of academic research, ways of marking time (both those used by archaeologists and by the ancient Maya), and a brief sketch of the conceptual and physical organization of Maya cities.effects that complement one another in layout and style.

Access a PDF of Houston and Inomata's "Introduction" here.

Although the chapter is an introduction, it sometimes references people or places that may be unfamiliar to you. If you come across one of these and want to know more, make a note. You can either include your question in this week's Canvas discussion forum or bring it up during our synchronous discussion.

What makes Houston and Inomata experts on the ancient Maya (i.e., how can we trust what they say about the past)? First, their expertise is immediately suggested by the university positions they hold: both are tenured professors of anthropology (Houston at Brown University, Inomata at the University of Arizona). The claims they make are also bolstered by their decades of experience in their field. They have each led important excavations at Maya archaeological sites (Houston at Piedras Negras, Kaminaljuyu, and El Zotz, Guatemala; Inomata at Aguateca and Ceibal, Guatemala, and currently in Tabasco, Mexico). Most importantly, they both have long records of publications that have been reviewed and vetted by other experts: books and edited volumes with university presses (several authored together) and articles in scholarly journals (ranging from international interdisciplinary outlets like Science to disciplinary-specific publications like RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, to regional outlets like Ancient Mesoamerica).

2. John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan

Following Houston and Inomata's overview, turn to the selection from John Lloyd Stephen's Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan.

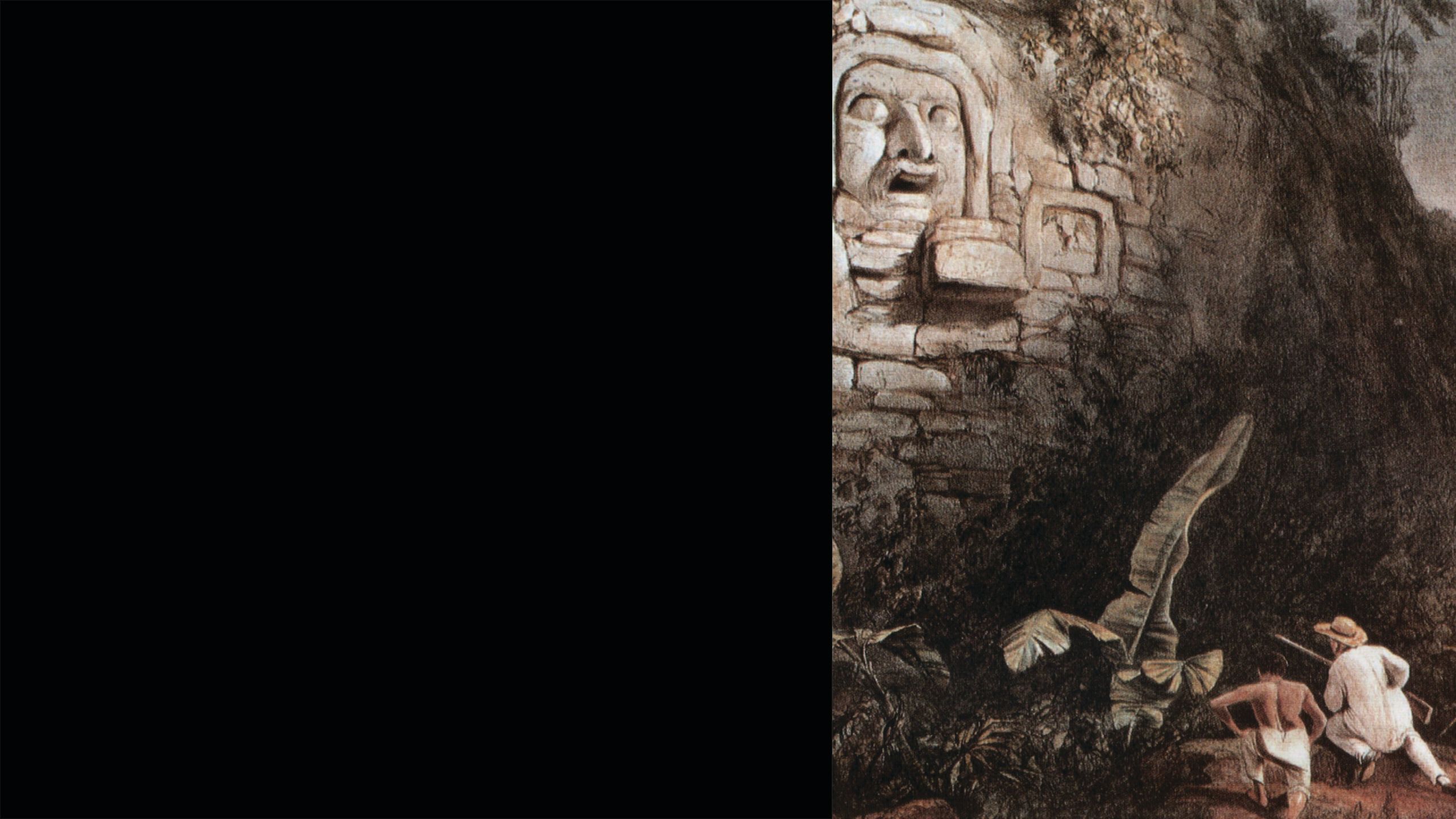

John Lloyd Stephens was a 19th-century American lawyer, travel writer, and diplomat. Before journeying through Central America with the British architect and avid traveler Frederick Catherwood to document ancient Maya ruins (between 1839-1840 and again between 1841-1842), Stephens had already published other popular accounts of his travels: Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia Petraea, and the Holy Land (1837) and Incidents of Travel in Greece, Turkey, Russia, and Poland (1838).

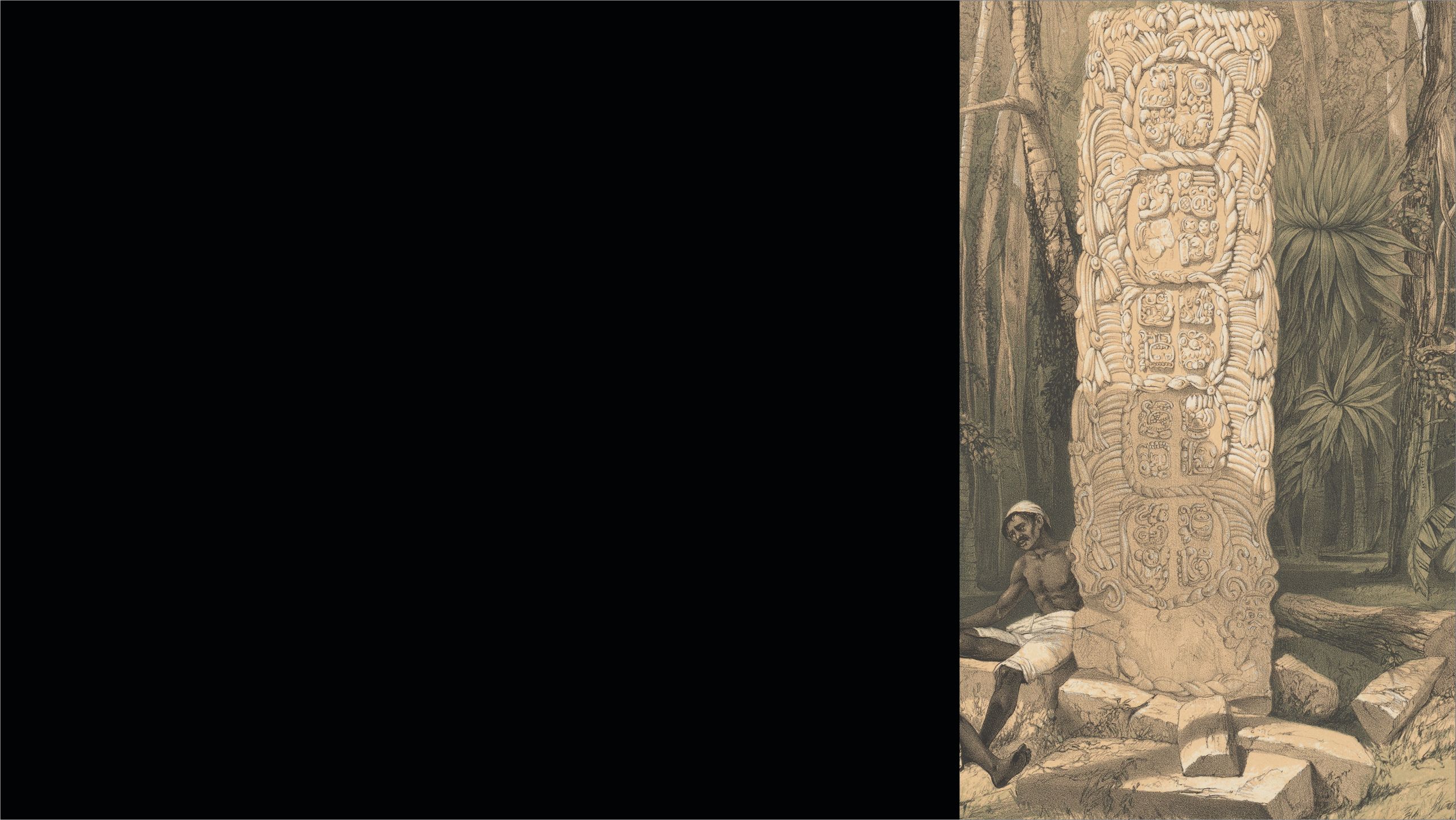

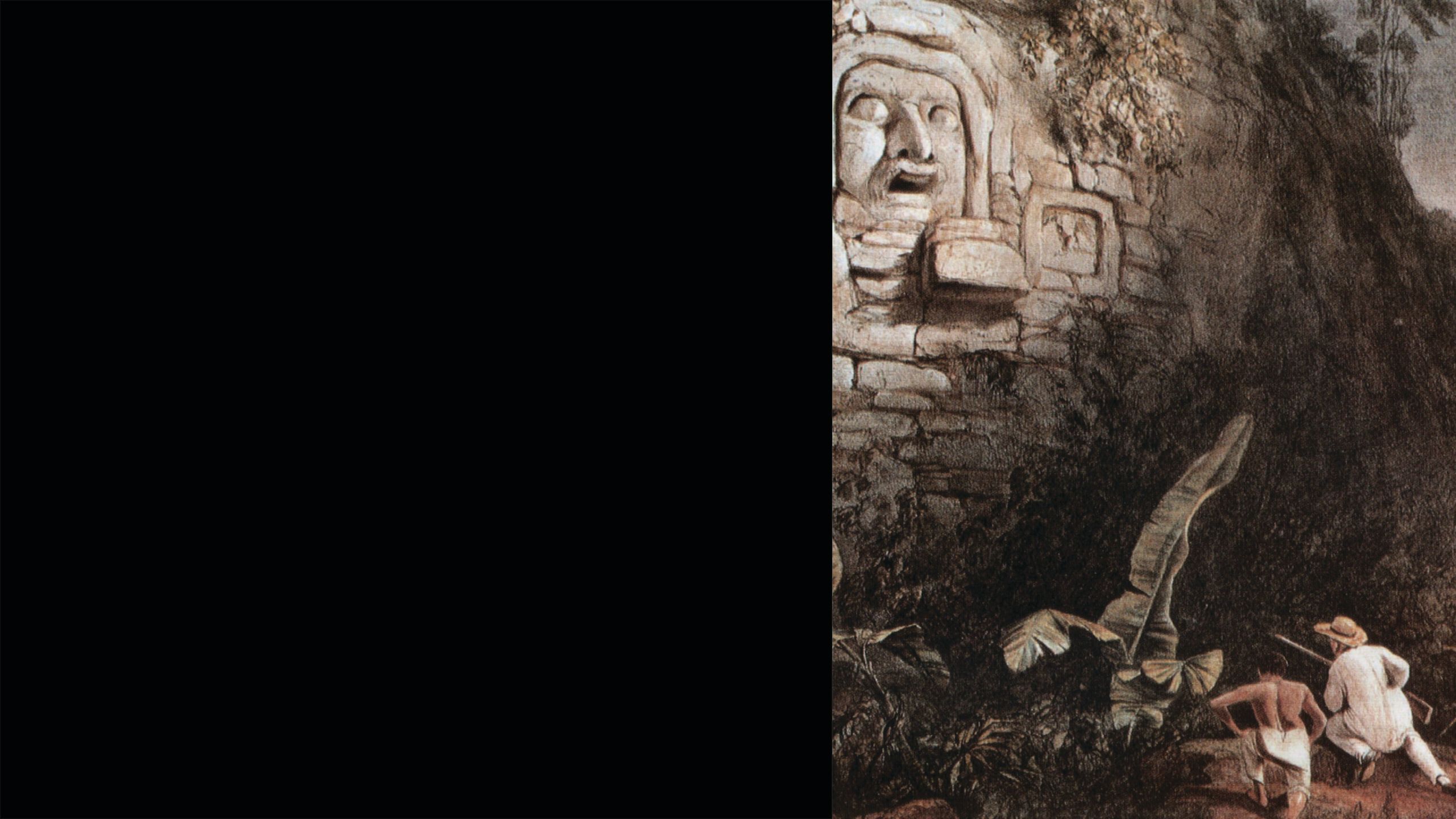

Accompanied by Catherwood, however, Stephens's Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (1843) stood apart. The volumes featured two hundred engravings based on Catherwood's original drawings, documenting Maya ruins from Copan in the south to Chichen Itza in the north. Catherwood used a camera lucida—a portable optical device that projects an image onto a surface—to aid in sketching Maya ruins. With the combination of the camera lucida and a skilled hand, Catherwood produced drawings that are remarkably accurate in perspective and precise in detail. Stephens's account and Catherwood's images focused international attention on the ancient Maya for the first time (not only have many local people always shown an interest in the ruins, but Stephens's own curiosity was sparked by earlier reports and drawings made on behalf of the Spanish and Central American governments).

Sadly, only a few of Catherwood's original drawings survive (now in museums and private collections). Most were destroyed in a fire while they were on exhibit in New York City in 1842, alongside several carved wooden lintels and other artifacts that Stephens had brought back from Central America.

As you read, pay attention to the ways in which Stephens narrates moments of discovery, interactions with local communities, the types of work being carried out, and the methods employed. Consider Stephens's aims and audience in the context of the moment in which he was writing. What is he trying to prove and to whom? How might his account be received by a reader in New York or London in the mid-nineteenth century?

Access Stephen's Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, Volume 1 here. (Note: you are only responsible for reading pages 101-105, 117-129, and 158-160 and to skim 134-158 for the engravings of Catherwood's sketches.)

Evident throughout Stephen's account is his sense that Maya ruins were abandoned and languishing in decay in the 19th century. He even purchased the site of Copan for US $50, with the hope of creating a "national museum of American antiquities" by dismantling and shipping the ruins back to New York in pieces. Like many antiquarians of his time, Stephens saw no connection between the Maya peoples he encountered during his travels and those who had built the temples and carved the texts that he so admired.

On the other hand, Stephens's far-flung travels also enabled him to recognize (contrary to accepted scholarly opinion at the time) that what we now call ancient Maya civilization was not simply the result of diffusion from Mesopotamia or Egypt, but a culture with independent origins; its own systems of kings and queens, nobles and warriors; and its own monuments to history in a yet-undeciphered script. Remarkably, many of Stephen's common-sense comparisons would be forgotten by later generations of Maya archaeologists.

3. (Optional) Augustus Le Plongeon, Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx

One of the optional readings for this week, the preface to Augustus Le Plongeon's Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx, offers a taste of the many eccentric theories about the Maya espoused by Stephens's contemporaries. Le Plongeon was an amateur British-American archaeologist who, always accompanied by his wife Alice (twenty-five years his junior), traveled to and excavated at Maya archaeological sites in Yucatan in the late nineteenth century. Claiming an ability to read ancient Mayan inscriptions, Le Plongeon crafted an elaborate and eccentric narrative around a particular statue he and Alice unearthed at Chichen Itza: a story of love, hate, jealousy, and murder among three brothers who ruled the ancient nations of Central America and the beautiful and powerful Queen Móo. In contrast to the idea that the Maya civilization was the result of diffusion from the Old World (the accepted wisdom at the time), Le Plongeon reversed that thinking, arguing that the Maya Queen Móo and the Egyptian Isis were one and the same and that the Egyptian sphinx was a monument built by Queen Móo to honor her husband (murdered by his brother).

Access Le Plongeon's Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx here.

4. Marcello Canuto et al., “Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala"

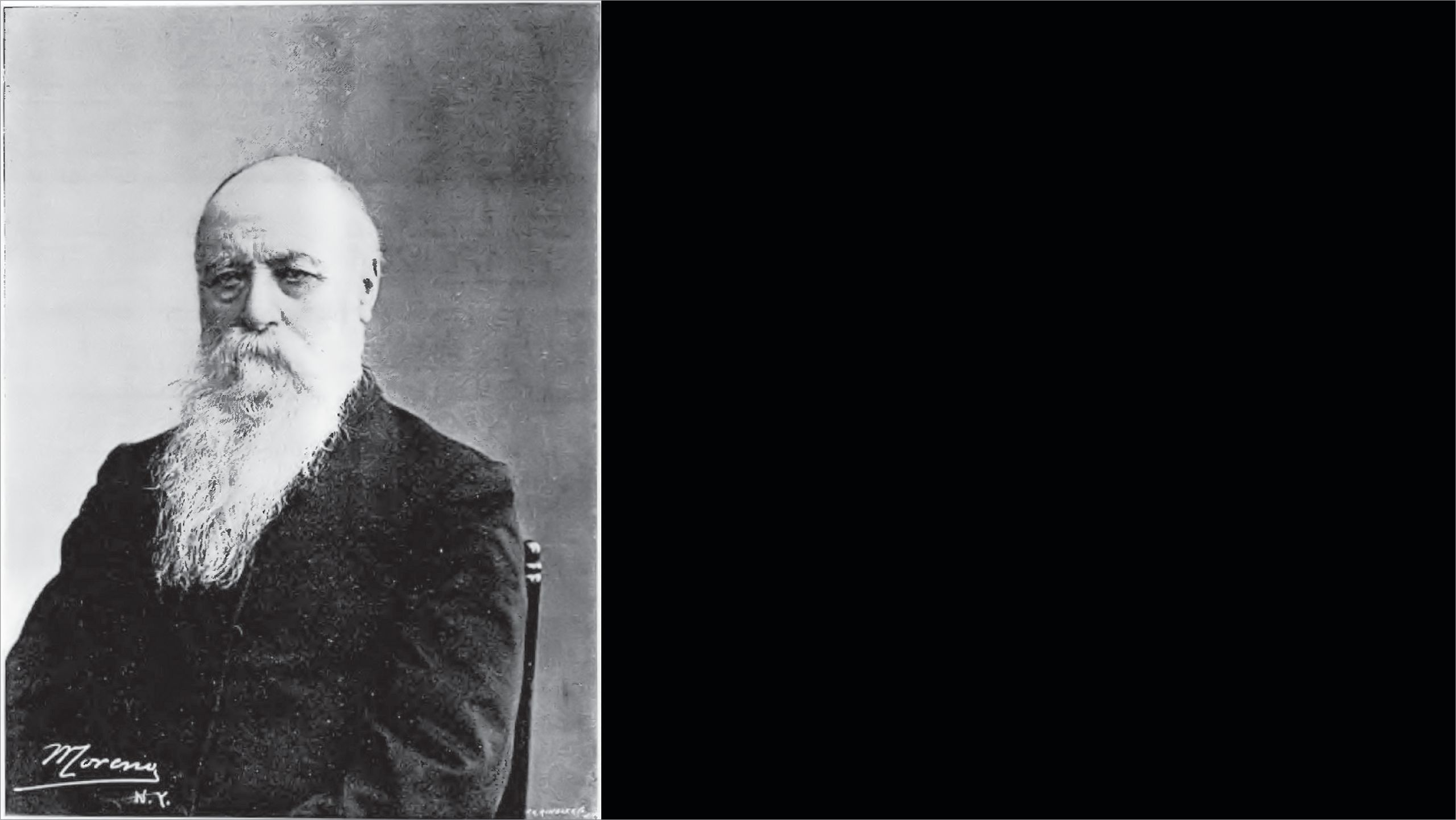

In the twenty-first century, Stephens's "impenetrable mysteries" are still echoed in Canuto and colleagues' description of a civilization "obscured by inaccessible forest." Airborne laser scanning surveys have recently made it possible to reveal ancient Maya infrastructure and settlement patterns across enormous areas of varied terrain. In this article, Canuto and his collaborators detail the advancements lidar provides over traditional mapping and survey techniques, identify new landscape features (including road networks, irrigation chanels, and defensive fortifications), and suggest radical new population estimates for ancient Maya civilization.

Access Marcello Canuto and colleagues' “Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala" here.

As you read this multi-authored piece, try to think carefully about the people and methods behind it. How did these researchers fund this expansive (and expensive) survey campaign? Take a close look at Figure 1 - what areas are covered by the survey and how are they related to one another? How is the kind of knowledge gained in this study similar or different to the kind that was produced by Stephens and Catherwood?

5. National Geographic, Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings

This National Geographic special is built around the PACUNAM lidar initiative (the same behind the Canuto et al. article - it spotlights some of the same co-authors).

Access National Geographic's Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings here.

As you watch the episode, consider the ways it presents the results of the airbone laser survey—particularly in comparison to the ways they were presented in the article published in Science. Think also about who and what is featured in the episode. What kind of portrait does it paint of how research is conducted in Maya archaeology?

6. (Optional) BBC Travel's “In Guatemala, the Maya world untouched for centuries"

This optional reading is an article that came out only a couple of weeks ago. In many ways, it closely echoes the narrative built by the National Geographic episode from two years earlier. If you choose to read it, consider how this article underscores certain tropes that are used and reused, not only in Maya archaeology, but in presenting Maya archaeology to a public audience. What are some of the common refrains found here, in the National Geographic special, and even as early as Stephens's account?

Access Amanda Ruggeri's "In Guatemala, the Maya world untouched for centuries," here.

Reviews of Shorthand Pages

Choose a case study from the Shorthand website or the company's Pinterest board and evaluate the page's success as a form of communication, paying attention to the use of the platform’s features, the relationships between text and imagery, and the narrative structure. (Note: the case studies on the Shorthand website provide descriptions of how organizations have created Shorthand pages, while the Pinterest board will lead you directly to examples without commentary).

You should upload a review of about 250 words (about one double-spaced page) to the assignment in the October 6 Canvas module (you may also include notes/screenshots/etc. as you like). During this week's synchronous class meeting, we will discuss your reviews and consider together what components make engaging, informative, and attractive pages.

Breakout Group Activity: Maya Ruins and the Passage of Time

As mentioned above, most of Frederick Catherwood's original drawings were destoyed by a fire in 1842. Catherood did publish twenty-five lithographs based on his drawings, however, in an 1844 volume called Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan, which includes an introduction, a series of descriptions of each of the monuments illustrated, and color plates.

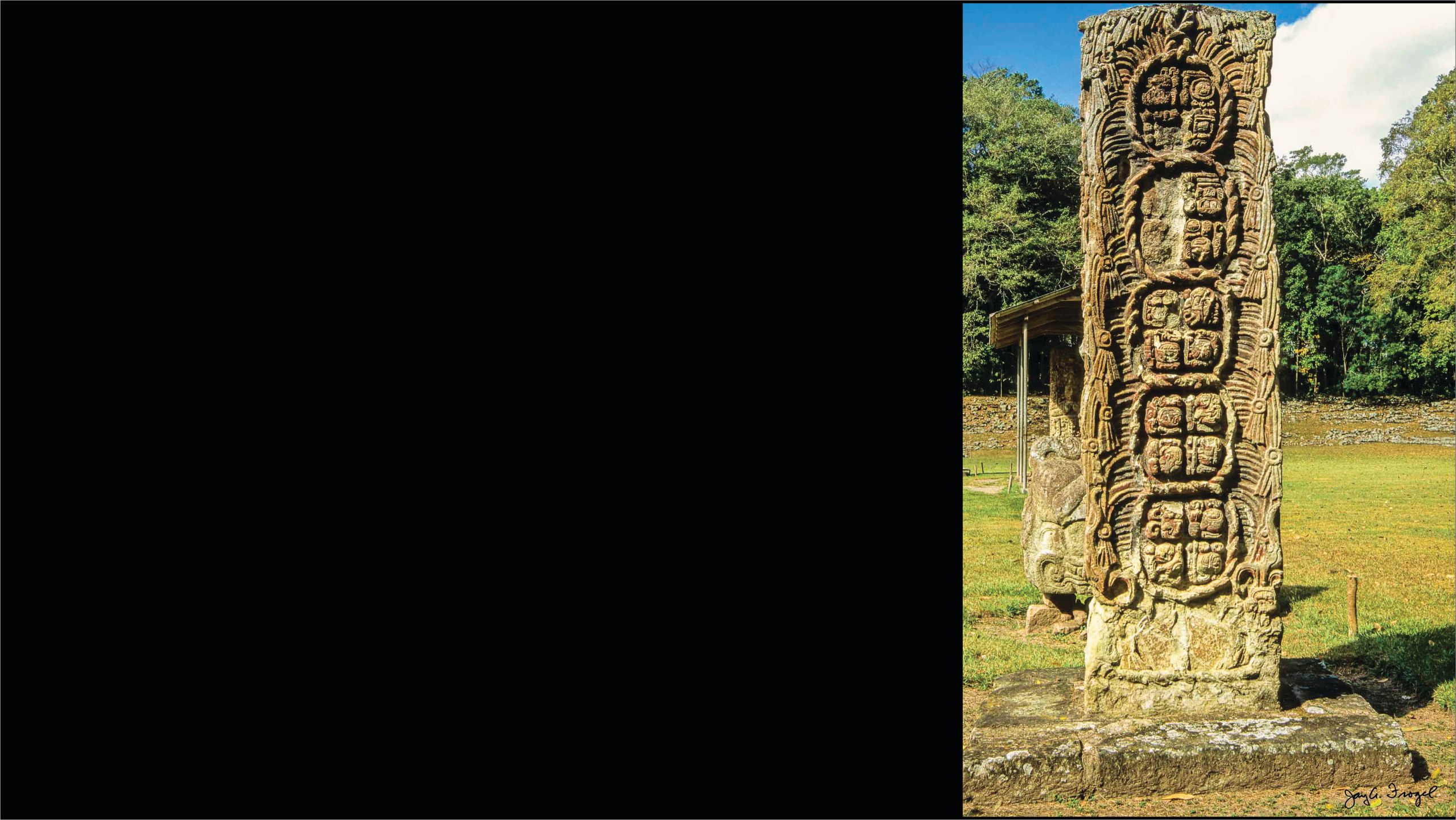

In 1998, a physicist and photographer named Jay A. Frogel became fascinated with the accuracy of Catherwood's images. Frogel followed in Catherwood's footsteps, returning to the same Maya cities, to the same vantage points, to photograph the same ruins over a century later. Frogel then superimposed his photographs over Catherwood's drawings, demonstrating how the buildings and landscapes have changed over time.

You can view ten of Frogel and Catherwood's combined images and side-by-side comparisons here (see the list on the righthand side of the page). In this activity, you will work with a partner to choose a drawing from Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan that is not one of the ten listed in the Dumbarton Oaks interactive exhibition. You'll need to flip back and forth between the text accompanying the plates and the plates themselves to identify what part of what site is depicted in an illustration (remember, this is a digital scan of a publication from 1844!).

Access Frederick Catherwood's Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America here.

Once you have chosen an image, find your own contemporary comparison using Google Images, Flickr, Pixabay, etc. Rather than trying to re-create Catherwood's vantage point as Frogel did, choose an image that emphasizes a particular aspect of this then-and-now exercise (e.g., peoples' clothing, vegetation around the monuments, architectural reconstructions, etc.). Write a short (c. 100 words) explanation of your choices (both of the Catherwood image and of the contemporary photograph) and point(s) of comparison and upload it, along with the recent image (or a link to the image), to the Breakout Group assignment in the October 6 Canvas module).